Before the BEGINNING and after the END

Beyond the Universe; Rediscovering Ancient Insights

R.K. Mishraji was born on this day, Sept. 28th, 1932. He would have been 78 years old today. It is my privilege to review his first book titled, Before the Beginning and After the End before an august audience, all who have been touched by his persona in some way or the other between the Beginning of his life, and its premature End. However, just as this title gives us a feeling of continuity similarly, we can even today sense Mishraji’s presence amongst us through his immortal words. He was a prolific writer, thinker, journalist, politician, and, few people knew that he was a Vedic scholar and a profound philosopher too. Based on the deep-rooted understanding of his Guru Shri Motilal Shastriji and before him Shri Madhusudan Ojhaji, Mishraji continued the scientific analysis of the Vedas in his four books in English.The material is so vast and the contents so extremely erudite that to do justice to even one volume in finite time is a difficult task. As we will see now, Before the Beginning and After the End is a text replete with Vedic revelations and thus Mishraji has qualified its title further as ‘Rediscovering Ancient Insights’.

In keeping with the spirit of the author, I ‘begin at the end’ – “Reflections” is the last section of this Book, and here, in simple prose spanning seven pages, Mishraji has summed up the entire work succinctly, with the poetic flair of an Upanishadic Brāhman. It is almost like a Śūtra. Therefore, I begin at the end and will unravel a few key concepts looking for their thread through the entire volume:-

- Mishraji says, “I go back in time to the beginning. The whole universe is reduced to a speck. Matter, energy and space disappear. With the vanishing of these three, time also disappears. There is neither a beginning nor an end.”[1]

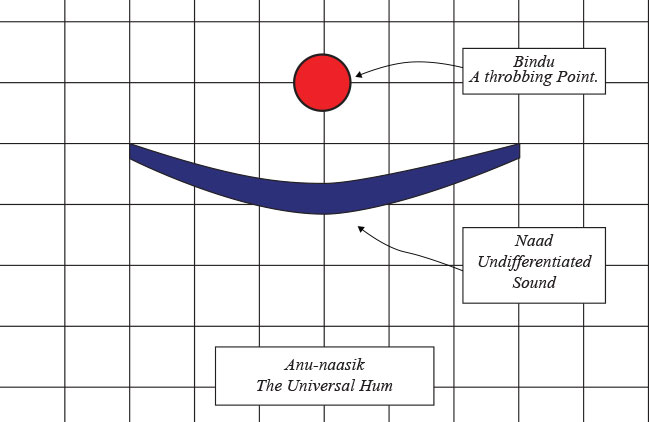

As we go back in time and reduce everything to a speck – we reach a state termed as Bindu in the Vedas . Mishraji explains [2] ‘Western scholars often translate Bindu in terms of mathematics as the ‘point’, which geometrically speaking is ‘zero’ dimension. It has no measurement, no length or width or breadth; but in terms of Hindu philosophy, Bindu is a ‘vibrant’ idea that is pivotal to all creation. The term Bindu, as per the Nirukta of Yaska muni, on the one hand can be derived from the root √bhid means to pierce, to cleave therefore it is like the concept of a hole. On the other hand, it also means Indu or a bright drop, a spark of light.’

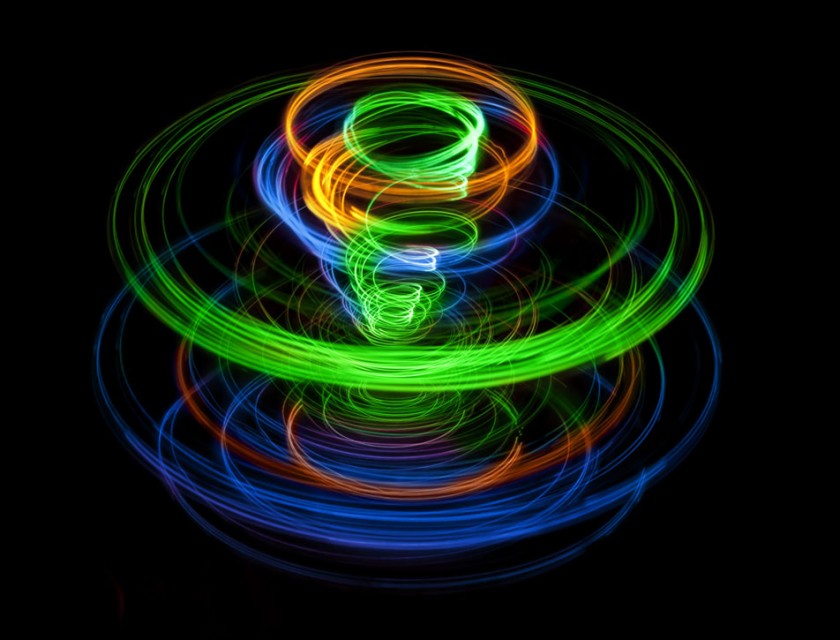

Thus, Bindu is representative of two opposing concepts – one a ‘hole’ in which all vibrations vanish, and the other a ‘bright spark’ that emanates energy. And this vibrating Bindu is the Spanda of the Shiv-sūtras of the Āgamas. Spanda literally means a ‘throb’, a pulsation of energy that spawns all creation. It is a concentrated microcosmic unit that unfolds to reveal all dimensions.

By the way, Mishraji explains that, the Āgama is generally mistranslated by scholars as ‘testimony or competent evidence’[3]. Āgama is more. It is actually the “cognitive process that, this true testimony, produces in the person receiving it”. It is the very act of understanding in the receiver’s mind, like the Sphota of Bhartrihari. Therefore, Mishraji concludes that even though Bindu is throbbing “it is neither a unit of time like kshana nor a space unit like the atom or Anu. Rather, it is a unit of consciousness, which at the same time, becomes the body of the material world.”

These words remind me of the idea of “point of choice” in the path breaking paper in Quantum Mechanics (QM) by Hugh Everett III who in 1957, as a 19 year old graduate student of Princeton University, came up with “The Many World Theory”[4]. This was to resolve the ‘Wave & Particle’ duality that is inherent in QM experiments at the sub-atomic level. At this level in QM, matter does not have a discrete nature – it remains in the realm of probabilistic wave energy emerging in the real world as a particle only when a conscious observer ‘looks’ at it.

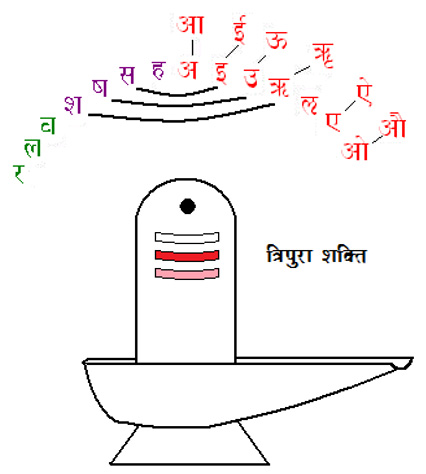

The Unknown in the Shiva- sutras is the Naad-Brahman, and this initial pulse is termed as the Naad-bindu. The adjoining diagram explains the Naad – ‘it is the generic potency representing all undifferentiated sounds’[5]. The latter is represented by the Chandra or ‘half-moon’ adorning Shiv’s matted hair. Together, they symbolize the anunasik or the ‘nasal-hum’. The anunasik is also the name of a class of letters in the last and fifth column of the table of mute-consonants in the Sanskrit alphabet. These letters are themselves five in number and are uttered through both the mouth and nose simultaneously. In the language this nasal sound when added to other consonants is indicated as a Chandra-bindu above the alphabet. This is the ‘hmm’ sound, at the end, as we pronounce ‘aum’ – the universal mantra of yogic chanting.

The Spanda or throbbing of this Bindu gives rise to the Shaktīs and their interplay unfolds the dimensions and multitudinous forms onto this mayanvic stage of the senses.

But before Mishraji takes us forward he explains in Chapter Ten – ‘God, Gods and Goddesses’[6] that the deities of Vedic thought are metaphorical constructs and they carry deep layers of metaphysical meanings. He exhorts us not to be misled by Western scholars and hurried translations but instead takes us towards the path of Sanatana Dharma. He says (quote) – “Sanatana Dharma is not a religion but an eternal path. This path is based upon the governing principles of the Universe. It is only when we do not view Sanatana Dharma as religion that the message and meaning of Veda Vijnāna or the Science of the Vedas becomes comprehensible.”

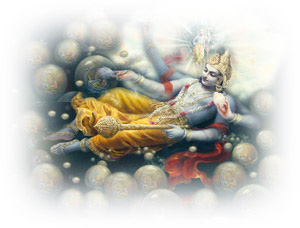

- So, now let us look at “Reflections” again for guidance and also use Motilalji’s ideas to develop this metaphysics. Mishraji writes, explaining the first moment of Creation of consciousness, (quote) – “How do I communicate this encounter? I etch the happening as Vishnu. Resting in the midst of an ocean (infinity), lying on the bed of a coiled serpent (the frightening turbulence of the physical universe) with his consort Lakshmi by his side.”[7]

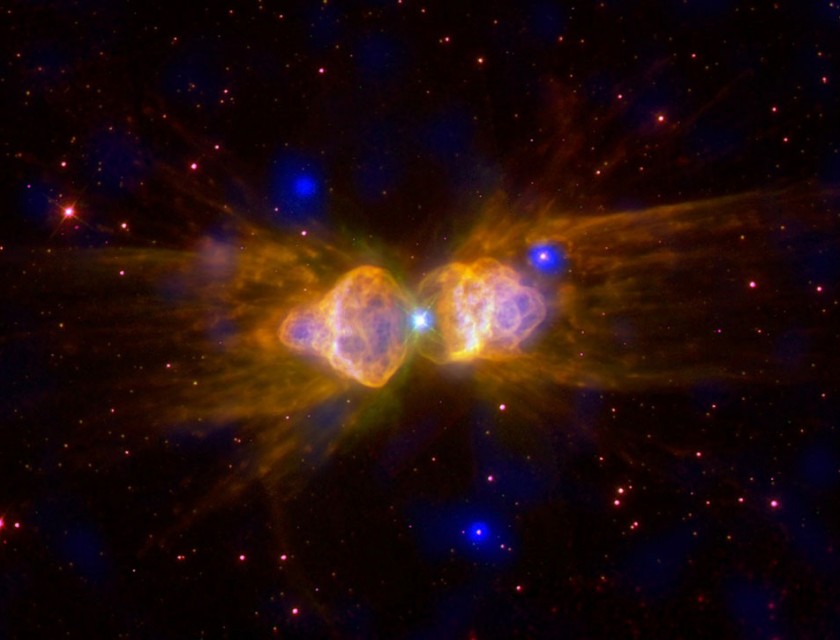

As we look outwards into the night sky, we see a vast ocean of energy. As our telescopes are getting better we see deeper into the space but further back into the time. But everything is moving… it is the jagatyām jagat of Ishopanishad. This incessant movement to our senses manifests as the dichotomy of Vishnu and Shiv. ‘Vi’ as a root means gati, vyāpti or ‘to speed away, flying away’ and ‘anu’ means ‘the tiniest form of matter’. Vishnu is therefore the expanding, emanating energy that is spewing out in discrete amounts from the supernovas at the galactic level and from the sun in our immediate solar system. Vishnu is all that shines in this luminous Universe.

As we look outwards into the night sky, we see a vast ocean of energy. As our telescopes are getting better we see deeper into the space but further back into the time. But everything is moving… it is the jagatyām jagat of Ishopanishad. This incessant movement to our senses manifests as the dichotomy of Vishnu and Shiv. ‘Vi’ as a root means gati, vyāpti or ‘to speed away, flying away’ and ‘anu’ means ‘the tiniest form of matter’. Vishnu is therefore the expanding, emanating energy that is spewing out in discrete amounts from the supernovas at the galactic level and from the sun in our immediate solar system. Vishnu is all that shines in this luminous Universe.

In terms of etymology Vish & Shiv are opposing forces. Shiv therefore represents the intense coalescing forces in the Universe. It is all the dark matter and its Shiv’s power that collapses the black holes to the center of each galaxy. But, closer at hand Shiva is the reservoir of the terrestrial energies. His abode metaphorically is the Mount of Kailash and he sits there with his consort Pārvati. The river Ganges entangled in Shiv’s flowing mane, at another level, stands for ‘Aakash-Ganga’ – the Sanskrit name for our galaxy ‘the Milky-way’.

Vishnu is often depicted with flames or agni emanating from Him and Shiv has snakes or nāgini around His neck. The root verb ‘ag’ means ‘a tortuous movement’ and the suffix ‘ni’ means in this context ‘to throw out’. So, agni is ‘the flickering of the flame’ that shines and spews forth energy. The opposite is na-agni or nāgini that means literally ‘a black tortuous movement’ that absorbs energy. And together their domain is called the Vishwa that is the entire visible and radiating Universe along with its ‘dark matter’[8]. Vishnu has many layers of meanings from the Supernovas, Quasars, Galaxies, billions of stars like our Sun and so on and so forth. Thus, in our myths, He has many representations like Adityā, Varun, Sūrya etc., and in fact, Mishraji has devoted an entire chapter in this book to “Vishnu and His One Thousand Names”[9]. Some are very powerful metaphysical concepts. Mishraji says, “Some of these names are masculine, some feminine and some neuter. Each opens a vista of ideas and inspires us to visualize a supraphysical factor which cannot easily be grasped by the tools of our understanding in their given state of development. Vishnu is the principle of consciousness which illuminates all experiences”.

Although Shiv has only 108 names in the Māhābhārata, the Shiv Purāna gives His thousand names. The Shiv-sūtras explain how the universal unfolding of the dimensions of Naad occurs in the I –consciousness. The best way of unfolding these as part of the karma of our daily lives is – kalā as Naṭarāj, gyān as Mātrikā and vikalpa as Yogi. And this is exactly what Mishraji means when he further explains the Āgama (quote) – “The goal of all these [lives’] activities is to discern the true nature and meaning of our [individual] existence – what we are, where we are, how we have come here and where we are going?”[10]

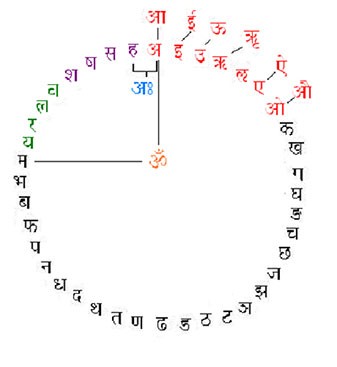

The expanding energies of Nād in theShiv sūtras are developed as the Mātrika Shakti or the study of the letters of the Sanskrit alphabet. A sūtra (viz. II.7) is mātrikā chakra saṁbodhaḥ. When we follow this and arrange the letters in a circle we get the Mātrikā Chakra [11] as shown. At the top where the Chakra closes the ‘ah’ sound forms and both the syllables ‘a’ and ‘h’ are kantasthah i.e. they are both uttered from the throat adjacent to each other. This ‘ah’ sound is also the bīja mantrā or ‘seed sound’ for the Sahasrār or the Crown Chakra. The ‘a’ is the ‘smallest syllable’ or the samvrt prayatna of the Aiterya Āranayaka; it is the indestructible Akshara or Brahmn. The ‘h’ is the aspirate or the sound of the exhalation of the breath. The Bindu completes the aham – and this is the I- consciousness. This Ātmā is born in the ‘sah’ world moving left and counter-clockwise around the Chakra. Clockwise[12] it is the hamsa the sound of our breath or prāna. It is not a mythical bird but rather a mantrā that we all chant compulsorily 8 to 10 crore times over a normal life time. When we die ‘yama’ transmits the hamsa to the world of ‘mara’ and while we live in ‘sah’ all the māyā unfolds in the dimensions of space-time and consciousness. The latter is the ‘yama’ reversed with lengthened svars as the extension in time.

The expanding energies of Nād in theShiv sūtras are developed as the Mātrika Shakti or the study of the letters of the Sanskrit alphabet. A sūtra (viz. II.7) is mātrikā chakra saṁbodhaḥ. When we follow this and arrange the letters in a circle we get the Mātrikā Chakra [11] as shown. At the top where the Chakra closes the ‘ah’ sound forms and both the syllables ‘a’ and ‘h’ are kantasthah i.e. they are both uttered from the throat adjacent to each other. This ‘ah’ sound is also the bīja mantrā or ‘seed sound’ for the Sahasrār or the Crown Chakra. The ‘a’ is the ‘smallest syllable’ or the samvrt prayatna of the Aiterya Āranayaka; it is the indestructible Akshara or Brahmn. The ‘h’ is the aspirate or the sound of the exhalation of the breath. The Bindu completes the aham – and this is the I- consciousness. This Ātmā is born in the ‘sah’ world moving left and counter-clockwise around the Chakra. Clockwise[12] it is the hamsa the sound of our breath or prāna. It is not a mythical bird but rather a mantrā that we all chant compulsorily 8 to 10 crore times over a normal life time. When we die ‘yama’ transmits the hamsa to the world of ‘mara’ and while we live in ‘sah’ all the māyā unfolds in the dimensions of space-time and consciousness. The latter is the ‘yama’ reversed with lengthened svars as the extension in time. Thus, we have seen how Bindu, a unit of consciousness unfolds its Spanḍa into the metaphysical duality of Viṣh & Shiv as it itself metamorphoses to the individual I-consciousness. The Visarga[13] is the prateek of the Ātmā and also in the Sanskrit alphabet it is considered as ayogavāh, literally meaning ‘outside the harness’.

Thus, we have seen how Bindu, a unit of consciousness unfolds its Spanḍa into the metaphysical duality of Viṣh & Shiv as it itself metamorphoses to the individual I-consciousness. The Visarga[13] is the prateek of the Ātmā and also in the Sanskrit alphabet it is considered as ayogavāh, literally meaning ‘outside the harness’.

- In this section, we look at the three Shaktīs or Goddesses Shri Lakshmi, Pārvati (Uṣhā) & Saraswatī. They have been deified respectively as the consorts of the Trinity of the Hindu pantheon viz. Vishnu, Shiv & Brahmā. But, as we shall see, they are actually deep metaphysical entities that are the key to understanding how the Ātmā experiences the infinite mysteries of life through its conscious evolvement.

But, before we proceed, I would like to quickly familiarize you with the Mātrikā Chakra. We will follow Mishraji’s advice at the beginning of his Book (quote)[14] – “The seer-scientists [rishīs] find a striking parallel between the origin and unfolding of this vast Universe and the process of development from the primal sound to the alphabet, words, sentences and, ultimately, the fully developed language. It may be compared to the evolution of a small seed into a huge banyan tree… Sanskrit meticulously follows the laws of nature in its evolution…”.

The Mātrikā Chakra consists of thirteen Vowels or Svars; twenty-five Mutes or Sparsh; four Semi-vowels called Antaḥstḥaḥ and the Sibilants or Uṣhman – the Shaktī symbols. The letters ‘sh’, ‘shh’ & ‘sa’ are the first three sibilants. The fourth is ‘h’ that, as we have seen, is the aspirate and represents the prāna.

The Svars or Vowels are the ‘pure sounds’ and derived from ‘svarna’ or gold, they are the ‘shining sounds’. The Vowels are likened to the energies of the day and the consonants to the night.[15] The ‘a’ if suppressed, and treated as the Unknown, the Unseen Brahmn it leaves us with 12 signs. These are the number of months or the sun-signs. ‘a’ is further embedded as a suffix in every mute and sibilant directly [16] and in the semi-vowels inherently – thus it constitutes every spoken word, sentence and gets integrated into the very fabric of all that shall be named in our conscious Universe.

The ‘h’ sound is also present in every alternate Mute or Sparsh, leaving the Anunāsiks or Nasal-stops. Of these twenty balance Sparsh (ka, kha, ga, gha, cha, chha etc.) the ten without the aspirate are alp-prāna, while the ones with the aspirate are called māhā-prāna. The primary svars are ‘a’, ‘i’, ‘u’, ‘ri’ & ‘lri’. (The latter is rarely used in literature). The first three ‘a’, ‘i’, ‘u’ are the fundamentals since to pronounce them the tongue is not deflected. (The same is true also for the aspirate ‘h’). ‘ri’ and ‘lri’ are half-way between vowels and consonants since the tip of the tongue is used in pronouncing them.[17] In fact the Śiva Sūtras [18] terms these two vowels as ṣhandaḥ or eunuchs. All these five vowels are of single sound i.e. of one mātrā. As these mātrās or long and protracted sounds come into play, the chhands are formed and we will look at these again later.

With the addition of the ‘a’ and ‘h’ sounds, the Mutes become twenty seven and this is the number of the lunar constellations in the Vedic system [19]. Each constellation marks thirteen degrees and twenty minutes of arc in the zodiac.

The Semi–vowels are the Antahsthah for they reflect the inner energies. Their significance in the body Chakra system of Tantrās is that they comprise the bīja mantrā for the lowest four body Chakras viz.’ya’ for the Heart or Anāhat Chakra ; ‘ra’ for the Navel or Maṇipūra Chakra ; ‘va’ for the Genitals or Swādhisthān Chakra ; ‘la’ the lower Pelvic or Mūlādhāra Chakra. The interesting symmetry in these Antahsthah is that their sounds are structured by the reverse combination of ‘a’ with the rest of the four primary svars. This is somewhat like the combination of the nucleotides C, G, A and T in the DNA structure.

We have seen here how an isomorphism from external reality to discursive language has been created. Thus, as we speak the first vowel ‘a’ to the last mute ‘ma’ – the glottis to the labials are traced and the entire mouth is virtually ‘shaped’ in the varṇas or letters. This is the universal ‘aum’.

Before getting to the Shaktīs we will look at one more concept – the western idea of infinities.

In “Reflections” Mishraji writes (quote)[20] – “Nothingness is zero – Shūnya. It is infinity. Add zero to zero. It remains zero. Subtract zero from zero. It remains zero. Add infinity to infinity. It is infinity. Subtract infinity from infinity. It remains infinity. This infinity becomes finite and marks the beginning. Every finite object ultimately is subsumed in the infinite. It marks the end.”

[21]On the mathematical side in 1870, George Cantor (1845 – 1918) gave us the ‘set theory’ – a brilliant thesis on the study of collections of numbers, points, objects, anything really in general. This revolutionized ‘number theory’ and gave rise to his– ‘Theory of Infinities’ or what is more precisely called ‘Cantor’s theory of Transinfinite cardinals’. The word transinfinite here maybe understood as a condensed form of transcendental Infinite – that which is beyond the infinite. How is this possible? Let us, at this point, push our limited reasoning on the lines of Cantor and attempt to explain this brilliant equivalence between – mantrā and math.

The ‘lazy eight’ symbol ‘∞’ has long been used to denote the infinite since this shape can be traversed endlessly.

Till the mid 19th century the only concept of infinity, in the mathematical world, was linked to ‘countable numbers’ or integers or natural numbers – as they are commonly known. As we count we go:-

1, 2, 3, 4,…..n…….. ∞ (‘natural numbers’)

Here ‘n’ stands for any countable integer. At the end of this seemingly endless sequence the number becomes too large to count and is denoted normally by ‘∞’. Cantor called this set א0 (Aleph–nought) a “countable infinite set”. Now obviously if we add or subtract any number from א0 it remains unchanged i.e. א0 +1 = א0

Not only this א0 + א0 is just א0: this is the very definition of infinity!

Not only this א0 + א0 is just א0: this is the very definition of infinity!

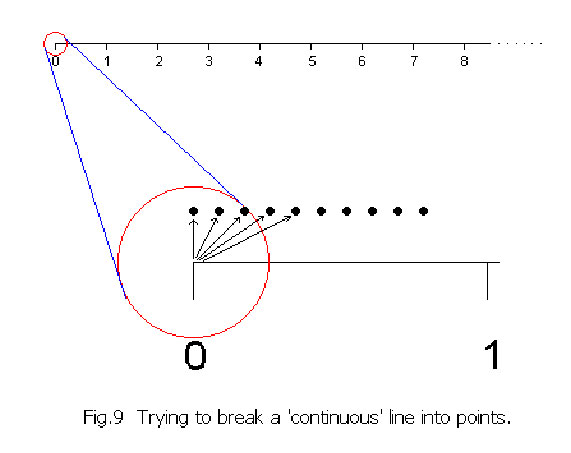

The earliest limitation of this way of thinking was probably expressed by Euclid (330–275 BC) when he tried to answer the question – “How many points are there in a ‘line segment’?” Now a line is a ‘line’; it is continuous and how can we talk about it as ‘discrete’ points? But then, that is what mathematicians are all about; they question what seems obvious and keep building a pyramid of well-grounded higher knowledge. In fact Euclid’s axioms and theorems are even today part of elementary school Geometry. But he could not answer this one!

René Descartes (1596–1650) had developed the idea of graphical representation, whereby, he had represented ‘real numbers’ by the length of a line and defined a co-ordinate system accordingly. Thus a horizontal line can represent ‘real numbers’ from zero onwards.

Cantor pushed his mathematical reflections on set theory and the ‘infinitely many’ further. He showed that there exist sets with an ‘infiniteness’ which is ‘beyond countability’. For this purpose, Cantor used a line segment as a measure for ‘real numbers’. Whereas ‘natural numbers’ belong to the sequence 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on.. the ‘real numbers’ are those which are integers with a decimal placed between them somewhere e.g. 1.291 or 0.3125 or 365.89 and so on and so forth. These are also known as decimal numbers. In real life, we use ‘real numbers’ for measurements, weights, scientific calculations, cash transactions etc.

Cantor showed that if we take, let us say, just the line segment from ‘zero’ to 1, we have a set of numbers like:

a1 0.1 3 5 8 6 4 3 2 …….

a2 0.3 6 4 9 2 5 4 1 …….

a3 0.2 8 7 2 1 6 3 6 …….

a4 0.8 3 1 5 7 6 4 2 ……. Ω

a5 0.7 1 4 3 1 8 5 7 …….

a6 0.6 2 4 7 8 3 1 9 …….

a7 0.4 3 7 6 3 9 4 5 …….

a8 0.3 6 7 2 8 9 8 9 …….

And so on,

Cantor then rigorously proved using his famous “diagonalization proof by contradiction” that whereas our numbering system on the left a1, a2, a3, ….. belongs to the set א0, the set of numbers on the right will always have more members and is a Higher set. This set is continuous and Cantor called it the “indenumerable infinite” which he named א1 (Aleph-one).

A corollary to this is also very interesting – Cantor proved that the set of fractions like 1/2, 1/3,1/4, 1/5 …… 2/3, 2/5, 2/7, ….. 3/4, 3/5, 3/7 ……. and so on, also belong to the “countable infinite” set א0 and even though this א0 is removed from א1 this “indenumerable infinite” set is not diminished. That is א1 – א0 = א1 however many times we perform this subtraction. Every continuous line segment whether big or small, irrespective of size will have א1 points.

No wonder on the title page of his Chapter “Who is the I?” Mishraji gives the Shānti Pāṭḥ[22] :-

“Om poornan adah poornam idam, poornāt poornam udachyate, poornasya poornamādāya, poornam ewaawshishyate.”

That is whole; This is whole. That is Infinite; This is infinite. When the infinite is taken out of Infinity, What remains is Infinite.

Now, coming back to the Sibilants, the Vedās treat the idea of Shakti or energy very differently from the western scientific method. The Shakti unfolds as part of the individual consciousness. Its perception is always as a ‘movement’ a kriyā. The first Sibilant ‘sh’ is Shri Lakshmi. It is the countable infinite and belongs to the domain of א0. Here the energy transactions are conserved. It moves from one place to another without leaving anything behind. I give you money, it decreases with me but improves your balance. This energy is discrete.

The next letter is ‘shha’ and it signifies Ushā the Shakti that keeps getting replenished. ….the rays of the sun; the flowing rivers; the sprouting leaves are all examples of this form of Shakti. The reservoir of energy is so huge that we get a feeling of ‘continuity’ in using it. I go to the river and take a bucket of water, I get it but the river immediately fills up. This belongs to the domain of א1 and it is continuous. The third Sibilant ‘sa’ is Saraswati. It is the energy which increases by giving – the lighting of the lamps, the spread of knowledge and the abundant fruits and seeds of the plants and trees constitute this Shakti. It is this relentless increasing magnitude of Saraswati that leads one to the fourth sibilant ‘ha’. Saraswati is all those processes where the count increases exponentially. This increasing is the root √brih from which Brahmn is derived.

The third Sibilant ‘sa’ is Saraswati. It is the energy which increases by giving – the lighting of the lamps, the spread of knowledge and the abundant fruits and seeds of the plants and trees constitute this Shakti. It is this relentless increasing magnitude of Saraswati that leads one to the fourth sibilant ‘ha’. Saraswati is all those processes where the count increases exponentially. This increasing is the root √brih from which Brahmn is derived.

The trees are a good example of the balancing of all these three Shaktīs – the trunk belongs to Shri because they are countable. We could actually go about the task of numbering all the trees in the world. The leaves belong to the realm of Ushā. Their number keeps changing and replenishing, it is dynamic and continuous. But, if we were to ask how many fruits and seeds can grow on all these trees and how many more trees and seeds can subsequently grow? It is an endless task and this is Saraswati.

We are equipped now to truly appreciate the last passage from “Reflections” – Mishraji writes (quote)[23] – “I sketch consciousness as an enthralling Goddess; a finite figure on the limitless canvas of infinity. A sculptor carves her in stone. A painter draws her on the walls of a cave. These are efforts to convey the incommunicable. Ecstasy captured in a poem. Infinity secured in finiteness. The limitless sky caged within the confines of my mind. Indescribable beauty imprisoned in an image”.

- As we perceive the Universe these Shaktīs seem to be enmeshed in it in an endless layer of symmetries. However, from the largest galaxies to the smallest of atoms what we ‘sense’ is only their vibrations. From light to matter to stars it is all a big cauldron or kalash of rhythms.

“What is there before the beginning? What is there after the end?” Mishraji asks in “Reflections”. And then he answers in the same breath (quote)[24] –“There is a rhythm in the Universe. The planets move regularly. The stars ride their appointed paths. Everywhere, there is the Law of Rhythm. Everything conforms to that Law.”

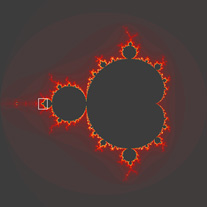

The rhythms of the Universe are non-linear. They merge mysteriously into each other. That which is linear lends itself to straight ‘cause & effect’. I push the pencil and it moves – this is linear. All machines are based on this linear mathematics. But in a non-linear world – the cause does not immediately come up with an immediate ‘effect’.

A push here may not result in an immediate effect there, the effects may collect over ‘space and time’ zones to precipitate entelechies, sudden occurrences or epiphanies which seem totally disconnected or small effects can cause huge changes.

In reality, all processes are cyclical, in that, the effects are again fed back to the original causes through various loops of energy[25] and this makes mathematical calculations by hand impossible. The global weather problem was the first non-linear equation to be widely studied and Edward Lorenz showed in 1963[26], how very small changes in weather patterns could precipitate huge changes thousands of miles away. He coined the phrase ‘the butterfly effect’ whereby he meant that a small butterfly flapping its wings in Peking could change the weather in New York. And this was prophetic indeed because the ‘El-Nino factor’ is now legendary. A small current in the Pacific has been empirically found to effect world weather.

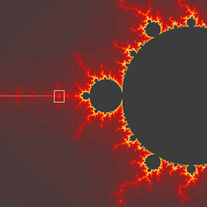

The advent of super-computers in the 1980s actually brought about the detailed study of these ‘Non-linear’ equations and this gave birth to the fields of ‘Chaos and Order’[27] and ‘Fractals’.[28] The western scientists and mathematicians saw that in real-world problems there was no absolute size. As you scaled the solutions, that is looked at bigger or smaller sizes the same forms and designs kept repeating themselves. There was symmetry within symmetry endlessly. Chaos Theory and Fractals are today being applied to just about every subject ranging from economics, share prices to study of heart beats. The list is endless.

Mishraji sums this up in a paragraph Sub-titled ‘From Linear Time to the Spiral of Time’[29] in his chapter on –‘The Space-Time Continuum’ (quote) –“The ancient Indian concept of time as described in the texts begins with its linear state, then moves on to the view of time as vertical spirals of circles. The circle becomes larger at each successive level in the spiral, subsuming the previous circle. As we move from the base of the spiral to the successive higher circles, we are called upon to widen our comprehension.”

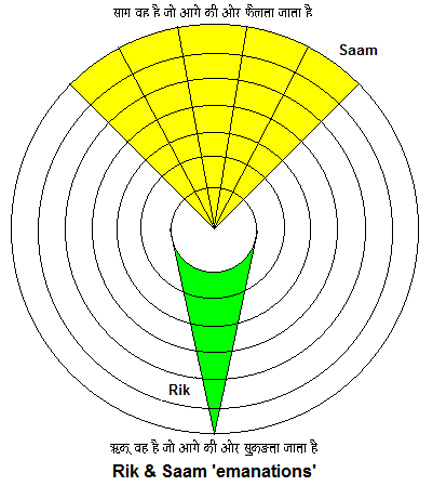

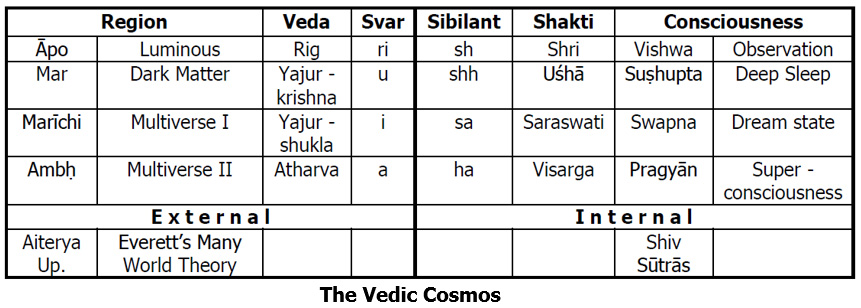

Now let us see how this ‘comprehension’ that Mishraji talks about happens. In the visible universe, there are symmetries within symmetries like Chinese dolls. [slide] But however large or small, we may improve our external senses we, as humans, are still restricted to the realm of ‘Āpo’. Motilal Shastriji explains this ‘first layer’ as – all that is vyāpak[30] and the knowledge for this layer is governed by the richāein of the Rig Veda. These rik emanations converge as they move outwards in this vyāpak Universe[31] and this is the ‘ri´ Vowel of the Mātrikā Chakra. The inward emanations into the mana or mind are the Sām and they expand as they enter inwards into our consciousness. Every time we observe something that is part of this external reality or this vyāpak realm it is stored as bits of information in our minds. However large this information maybe over a lifetime these bits and bytes are part of the ‘countable infinite’ ‘sh’ and are stored in the first layer called Vishwa of our consciousness. Thus ‘sh’ and ‘ri’ combine to give us Shri. This observational knowledge is Yantrik.

The next two layers are Mar & Marīchi[32] and governed by the Yajur veda – krishna (dark) and Yajur veda – shukla (light) respectively. Motilal Shastriji writes that the word Yajuh is the combination of both the vowels ‘i’ and ‘u’.

The Mar region is the non-visible region where the ‘dark matter’ exists and since it is not directly visible or vyāpak – it can only be inferred. This is the letter ‘u’. This is the Pitrlok externally and all these measurements in the mind internally can be confabulated upon creating a higher combination of infinities. Here, we build upon the observational part by continuous vimarsha. This region is the Sushupta, the next layer of our internal consciousness. It is akin to deep sleep where all the continuous processes of the body and mind connect. These connections belong to the higher ‘ind-enumerable infinite’ ‘shh’. Thus, the svar ‘u’ and ‘shh’ combine to give Uṣhā and the whole body of knowledge called Tantra comprises this domain. Thus from ‘sh’ to ‘shh’ we go by vimarsha.

From ‘shh’ to ‘sa’ the consciousness moves using gyān or insight and perception. This region can conjure up any number of combinations of ideas and interpretations and is therefore the Swapnalok. Literally the ‘dream world’ that can be ‘observed’ only by ‘inner light’ or driṣṭi. The knowledge of this region is externally contained in the Yajur veda – shukla and the region is Marīchi. This is the divyalok, the realm of the Devtās of Hindu mythology. It is equivalent to the Multiverse-I region in Tegmarks[33] explanation of Everett’s “The Many World Theory”, cited earlier. This is the ‘higher’ realm where all desires exist as ‘probabilities’ and only few gifted persons like the icchādhārī Yogīs can use it to make desires manifest. It is represented by the vowel ‘i’ and along with ‘sa’ it is Saraswati.

What we have outlined just now is also part of the Śri Tripura Rahasya and Mishraji has devoted the entire Chapter Eleven – ‘Pure Intelligence and Absolute Consciousness’[34] to this.

In “Reflections,” Mishraji talking about consciousness says (quote) – “Consciousness marks the beginning. Consciousness of existence. Existence of objects. Consciousness of men and women, children and the aged, buildings and roads, birds and animals, mountains and oceans. As if vacant space has been filled with numerous objects…. The Universe is in consciousness. Consciousness is in the Universe. Consciousness is in the Cosmos. The Cosmos is in consciousness.”[35]

The very use of the two words – “Universe” and “Cosmos” distinctly shows the author’s attunement to the worlds beyond.

In the table below, I have given the summary of the information of this section so that we can finally look at a pictorial representation of the Tripura.

Looking at the Mātrikā Chakra, we see that as the three Shaktīs are connected from their Sibilants to the respective Svars they outline the three Tripura lines on the Shiva Linga below the Bindu.

Quoting Mishraji at the end of this, he writes (quote)[36] – “Thus we find that the concept of the Goddess in Sanatana Dharma is profound. Tripura Rahasya helps the seeker to comprehend the incomprehensible abstract intelligence, or supraphysical energy, which underpins absolute consciousness. There is no mythology here, at least in the sense in which that word is commonly understood. The stories and dialogues comprising these and other narratives in Tripura Rahasya help the student to hone his or her tools of comprehension and to understand the subtle and complex forces, principles and phenomena of our Universe”.

- In establishing the basis for the Supraphysical study Mishraji establishes that Prāna, Mana & Wāk are the simultaneous and spontaneous divisions of the Ātmā. He writes in the Section – ‘When Divisions Arise’ of the Chapter – ‘Beginning the Journey’[37] (quote) – “This is the beginning of the process of creation, which transforms One limitless, indivisible entity into a three-dimensional one. The former is described as Brahmā; when divisions arise in it, it becomes known as Ātmā. The process of transformation involves three ‘elements’ which are always present in creation. The whole creation has emerged out of these three – Prāna, Mana & Wāk.”

We have already studied the first two and we have been introduced to the third as Mātrikā Chakra but now we look at Wāk in more detail in this Section. It encompasses all sounds, both spoken and heard, and to this is added the rhythm of meter or chhand & tāl.

Motilal Shastriji explains in his Vigyānbhāshyaṁ of the Shatpath Brahṁaṇā that as we look outwards from the Earth and talk to each other our view is termed bhūgolik or earth-centric and our speech is called Wāk. If we look from the heavens downwards, filtering the cacophony, we hear the natural sounds or what is called Dhwani or music. And this view is termed Khagolik. Thus Vāṇi is the ‘words that are sung’ and it is both Wāk and Dhwani put together. It is the Divine song.

The svars besides sound also contribute the measure of time, called mātrā, to the Wāk. A mātrā is ‘a prosodical unit of one instant’. Phonetically the Svars are of three types viz. short vowels or hrasva, – single meter; long vowels ordīrgha – dual meter and prolongated vowels or pluta of three stops. There are seven short vowels and with the dīrgha added, as we have seen earlier, they are thirteen in number. With the longer, three mātrā pluta versions of the vowels, the count goes up to twenty two.[38]

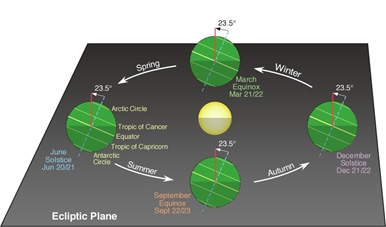

The consonants combined with these metered vowels give a rhythmic, chanting pattern called the mantrās and these rhythms have seven basic structures called chhands. Now, interestingly the basic count for the number of syllables in these chhands varies from 24 to 48 increasing in steps of 4. These are gayatri (24), ushṇik (28), anushtup (32), brihati (36), pankti (40), trishtup (44) and jagati (48). Pt. Motilal Shastriji has explained these in terms of how the Earth revolves around the Sun.[39] The Earth has a 24o (23.5o to be precise) tilt in its orbit. To us, therefore, the Sun appears to move from above the tropic of Capricorn to above the tropic of Cancer by an angle of 48o approx. in its annual swing. It is this degree of change that the Vedic chhands are attuned to and this is further underlined by the fact that the middle chhand is called brihati (36), meaning ‘the largest’ even though it is in the centre. This is because the Sun is the brightest at the Equator, in-between the two tropics.

The Vedic shlökas composed in various chhands are also called shrutīs. These shrutīs are said to have descended as direct knowledge into the heightened senses of the rishīs while they meditated upon the mysteries of the Universe. These mantrās have a cadence and they are accented. When a syllable is stressed it is called udātta , literally meaning acute or high. Then there is anudātta, which is neither high nor low, it is grave or middle. The latter is indicated in old Vedic texts by a line below the syllable. The last is svarita , which is low. This is marked by a vertical line over the syllable in the Vedās and Brāhmaṇās. These accents lead us to the musical notes of Dhwani.

The seven ‘lights’ in the sky are the Sun, Moon and the five planets visible to the naked eye. This symmetry is reflected into the Dhwani or music. The primary seven notes are sā, re, gā, mā pā, dhā, ni [40] which are also called svars or ‘the shining gold’, just like the vowels of the Mātrikā Chakra letters. If we take the first four notes we get the word Sargama or the name for the musical scale in the Indian classical system. It is these seven svars that bring about the accent in the chhands – ga and ni are udātta; re and dhā are anudātta and sā, mā, pā are svarita. Thus, when the mantrās are chanted, it is these musical notes that are followed.

Spaced between these seven notes are four semi-tones or komal-svars viz. for re , gā , dhā and ni ; and only one acute-tone or tīvra-svar viz. for mā. The latter, like the chhand called brihati is in the centre of the scale. Added to the pure seven notes the count now becomes twelve and this again reflects the symmetry of the sun-signs.

Here too there are twenty two shrutīs.[41] In terms of music, shruti means the smallest discernible interval of pure sound. These shrutīs can be played on the dhruva veenā, an instrument with twenty two strings, but they are too many shrutīs to sing through the kanṭaḥ or the throat. Thus, all the present day rāgas are based on the selection of seven, six or five notes out of the twelve svars but largely based on the twenty two shrutīs ; each of the svars is constituted of two or three shrutīs. Thus there are thousands of rāgas, each having its own time of singing during the day or night and there are also seasonal rāgas. You are also allowed to go up the scale in one rāga and come down the scale in another. Thus an adept singer can synthesize this movement beautifully in a rendering. And this is called the āröha and the avaröha respectively.

The beginning and end note of all rāgas is called sam meaning uniform and this fundamental note at present is the shadaj or ‘sa’.

Interestingly of these twenty two shrutīs in the Indian music system, only one name röhinī is common with the names of the lunar constellations[42]. For the musical notes this name is in the division of the musical note dhaivat and is five shrutīs prior to shadaj. For the lunar constellations, röhinī is in Taurus and it was the vernal or spring equinox five to six thousand years back. (At present, the vernal equinox is in Pisces and will be moving into Aquarius around 2600 AD).This shift is due to the precession of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun and this circling takes about 26000 years to complete. Thus approx. every 1000 years the zodiac shifts by one lunar-sign. (It takes approx. 2200 years to shift by one Sun-sign). In Indian classical music the fundamental note too is shifted accordingly. Six thousand years earlier the fundamental note was five shrutīs earlier in dhaivat. In fact the name ‘shadaj’ itself means ‘born of the sixth’ [43]. Thus every 1000 years or so, the traditional vocal music gharānās or families are to correct the fundamental note of the rāgas by one shrutī to compensate for the precession of the Earth. This is another amazing terrestrial rhythm programmed into the Dhwani system thus finely attuning it to our daily life.

In this treatise I have tried to acquaint you with various intertwined aspects of the ‘triad’ of Prāṇa, Mana & Wāk as explained by Mishraji in this Book. I have tried to follow the style of his Guru Shri Motilal Shastriji in terms of Vigyānbhāshyaṁ or the ‘Scientific Method’. We have seen how Prāṇa arises via the throbbing Bindu and the Mana uses its intent to precipitate Wāk[44]. It is this precipitation or avaröha of Prāṇa that is called Praṇav and this is the ‘downward’ movement of the Shaktīs in our daily life– their unfolding into finiteness. ‘Om’, on the other hand, is the ‘upward’ movement of Prāṇa. It is the āröha of the Shaktīs and‘it is the mantrā that guides us back to the Infinite.[45]

Mishraji says (quote) – “Praṇav, the symbol of Brahmn or Supreme Reality, is the Truth behind creation (Ādi), sustenance (Madhyamā) and dissolution (Anta). One who has known Aum – which is soundless as well as of infinite sounds – is none other than the true seer”. And, S. Radhakrishnanji tells us that Truth or Satyaṁ is the finiteness of ‘ti’ bound by Infinity on both sides as ‘sa’ and ‘yam’.[46]

So if there is Infinity ‘before the Beginning’ and there is Infinity ‘after the End’ then, what helps us in overcoming the finiteness between the two? In the last line of “Reflections” Mishraji gives us the answer – “Love expressed in silence.”