Divinity in Sound

As the Vedic rishis sat in the serene foothills of the Himalayas, thousands of years ago, they meditated upon the mysteries of the Universe – the Unknown, the Brahman. Their silent minds were in complete synchronicity with the world around them – a unique unison of mind and matter. In this heightened state of Cosmic consciousness answers floated into their enlightened senses as shrutis or latent sound bytes. This was the origin of the Vedas. The mind was the laboratory and the Universal truth the subject. This is how the Unknown, Brahman revealed itself as the first shabd or word.

■■ The Maitri Upanishad [1] VI.22 explains this shabd as arising from a-shabd or non-sound. It says :-

■■ The Maitri Upanishad [1] VI.22 explains this shabd as arising from a-shabd or non-sound. It says :-

And it has been said, there are verily, two Brahmans to be meditated upon – sound and non-sound. By sound alone is the non-sound revealed….[2]

Shabd not only means the ‘spoken word’ but it also carries with it the eternal quality of the non-sound. This can be understood as ‘memes’, a concept put forth by Richard Dawkins [3]. He says words, besides pronunciation, carry abstract ideas and together he calls them ‘memes’. These ‘memes’ are “cultural transmission units” that go from memory to memory down the generations – just like the passing on of the genes.

Guru Nanak Dev in his teachings calls this the shabad . He has taken the ‘a’ sound of the negative prefix and incorporated it in the word itself , for he explains :-

shabad is the first sound, the first utterance

that created the universe, that was created with the universe

it is the discourse of the Guru

it explains and discerns, it articulates and animates

the eternal Truth of forms and concepts…[4]

The larger concept of sound is referred to as the vaani . It includes not only words but also rhythm (or meter) and tune. Speech is referred to as vaak in the Rig Veda ; at I.164.41 in this Veda vaak is likened to Gauri the benign Cow Goddess. As the cow walks about its many gaits so does speech take on various meters and forms, helping in the fashioning of words and in the spreading of the milk of happiness out into the conscious world.

The larger concept of sound is referred to as the vaani . It includes not only words but also rhythm (or meter) and tune. Speech is referred to as vaak in the Rig Veda ; at I.164.41 in this Veda vaak is likened to Gauri the benign Cow Goddess. As the cow walks about its many gaits so does speech take on various meters and forms, helping in the fashioning of words and in the spreading of the milk of happiness out into the conscious world.

These various meters of the Vedas are called the chhands. The Sanskrit shlokas unfold the sound energies as we view outwards from the Earth and talk to each other. This view is termed bhugolik or earth-centric and our speech is called vaak. If we look from the heavens downwards, filtering the cacophony, we hear the natural sounds or what is called dhvani or music. And this view is termed Khagolik. Thus vaani is the ‘words that are sung’ and it is both vaak and dhvani put together. It is the Divine song.

● Speech and music again come together as Goddess Saraswati. She is the consort of Lord Brahma and the word Saraswati is the combination of sara , which means ‘essence’ and swa, which means self. She, therefore, is the path to pure self-knowledge which in terms of Vedic tradition is also the knowledge of the Universe. Clad in white, she sits on an eightfold, white lotus symbolizing the realm of the Unknown. In her foremost two hands, she holds the veena, a musical instrument of dhvani for the accompaniment of the vaani . In one of the rear hands, she holds the Vedas signifying the spoken word or vaak. In her fourth hand, she holds a rosary indicating the returning inner path of meditation and the white swans or hamsa, by her side give us the mantra for this inward involution.

● The simple Sanskrit prose is the shlokas. The vowels are the first set of letters in the Sanskrit alphabet. They are called svars which literally means ‘pure sounds’. Svar is derived from svarnah the word for pure gold or from su + varnah meaning ‘a pure phoneme’.[5] The svars contribute the measure of time, called maatraa, to speech. A maatraa is ‘a prosodical unit of one instant’. These vowels, svars , are of three types viz. short vowels, hrasva, – single meter ; long vowels, dīrgha – dual meter and prolongated vowels, pluta of three stops. There are seven short vowels and if we add all the short and longer versions of the vowels the count goes up to 23.[6]

The consonants combined with these metered vowels give a rhythmic, chanting pattern called the mantrās and these rhythms have seven basic structures called chhands. Now, interestingly the basic count for the number of syllables in these chhands varies from 24 to 48 increasing in steps of 4. These are gayatri (24), ushṇik (28), anushtup (32), brihati (36), pankti (40), trishtup (44) and jagati (48). Pt. Motilal Shastri, a Vedic scholar of rare insight, has explained these in terms of how the Earth revolves around the Sun.[7] The Earth has a 24o ( 23.5o to be precise) tilt in its orbit. To us, therefore, the Sun appears to move from above the tropic of Capricorn to above the tropic of Cancer by an angle of 48o approx. in its annual swing. It is this degree of change that the Vedic chhands are attuned to and this is further underlined by the fact that the middle chhanda is called brihati (36), meaning ‘the largest’ even though it is in the centre. This is because the Sun is the brightest at the Equator, in-between the two tropics.

The chanting of the mantras uses three accents. When a syllable is stressed it is called udaatta , literally meaning acute or high. Then there is anudaatta, which is neither high nor low, it is grave or middle. The latter is indicated in old Vedic texts by a line below the syllable. The last is svarita , which is low. This is marked by a vertical line over the syllable in ancient Vedas and Brahmanas. These accents lead us to the musical notes.

- The seven ‘lights’ in the sky are the Sun, Moon and the five planets visible to the naked eye. This symmetry is reflected into the dhvani or music. The primary seven notes are sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni [8] which are also termed svars or ‘the shining gold’, just like the vowels of the Sanskrit language. If we take the first four notes we get the word sargama or the name for the musical scale in the Indian classical system. It is these seven svars that bring about the accent in the chhands – ga and ni are udaatta; re and dha are anudaatta and sa, ma, pa are svarita. Thus when the mantras are chanted it is these musical notes that are followed.

Spaced between these seven notes are four semi-tones or komal-svars viz. for re , ga , dha and ni ; and only one acute-tone or tivra-svar viz. for ma. The latter, like the chhand called brihati is in the center of the scale. Added to the pure seven notes the count now becomes 12 and this reflects the symmetry of the sun-signs.

Interestingly, while playing instrumental music the smallest ‘discernible interval of pure sound’ is again termed shruti .They are 22 in number. This is the finest scale of tones that can be comfortably played on the stringed instruments. One of these instruments is the dhruva veena, an instrument with 22 strings, which is the reference standard of the Indian music system. For, dhruva means ‘constant’ and is also the name of the ‘north-star’. The Carnatic music system of south-India still adheres to the shruti system for its daily vocal rendering.

All the present day ragas are based on the selection of 7, 6 or 5 notes out of these 12 notes. And in an Indian classical music composition you can go up the scale in one raga and come down the scale in another. This is termed as the aroha and the avaroha respectively. This gives us the possibility of hundreds of thousands of combinations – the ragas therefore change with the season, the time of day, location and so on. The multiplicity of the world around us reflects comfortably within this structure of the ragas and those who sing the Divine song are thus called the raagis .

A word on the rhythm. The regularity of the accent is the meter or chhand in the prose. In music the tempo is set by the interval between two regular beats and this interval is called the laya . Kaal is time and kalaa means an art form. The beat is therefore termed as kaal-kalaa or taal in short. This beat can be introduced through an external percussion instrument like the mridangam, pakhawaj or tabla etc. or the performer may maintain this tempo as laya in the playing or singing. The laya normally has three time-speeds viz. vilambit (slow), madhyam (medium) and druta (rapid). The number of beats can alter and the taals are so variously named – dadra(6) , rupak(7), kaharwa(8), jhaptaal(10), ektaal(12), teentaal(16) and so on. In ‘Sangitratnaakar’ [9], a 13th century exposition on music Sharangdeva rishi describes fully 108 taals. Incidentally, 108 is also the number of beads in the mala or rosary… and arithmetically 108 = 1 x (2×2) x (3x3x3).

The three components of vaani are, therefore, vaak, dhvani and taal(or laya).

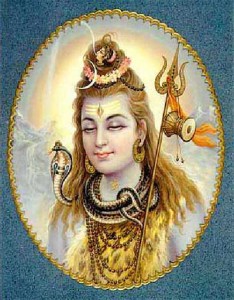

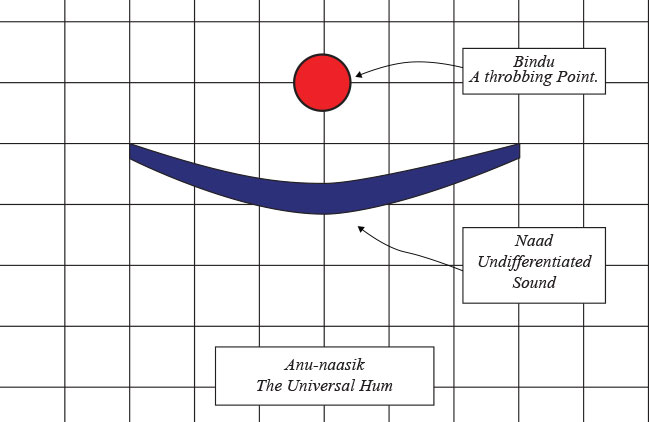

■■ In the Agamas literature of Hindu thought the ‘non-sound’ Brahman is referred to as the Naad-Brahman . At a more meta-physical level this is termed as Naad-bindu in the Shiva- sutras. These sutras or ‘condensed mantras’ were first revealed, in the late 8th century A.D., by Lord Shiva directly to Vasugupta on mount Mahadeva in the Kashmir Himalayas. Later expounded by his student Abhinavagupta, this philosophy came to be known as Kashmir Shaivism.

“Here bindu – ‘is a throbbing point of stress or a pulsation called spanda’ and Naad – ‘is the generic potency representing all undifferentiated sounds’”[10]. The latter is represented by the Chandra or ‘half-moon’ adorning Shiva’s matted hair. Together they symbolize the anunasik or the ‘nasal-hum’. The anunasik is also the name of a class of letters in the last and fifth column of the table of mute-consonants in the Sanskrit alphabet. These letters are themselves five in number and are uttered through both the mouth and nose simultaneously. In the language this nasal sound when added to other consonants is indicated as a Chandra-bindu above the alphabet. This is the ‘mmm’ sound, at the end, as we pronounce ( ! ) or ‘aum’ – the universal mantra of yogic chanting.

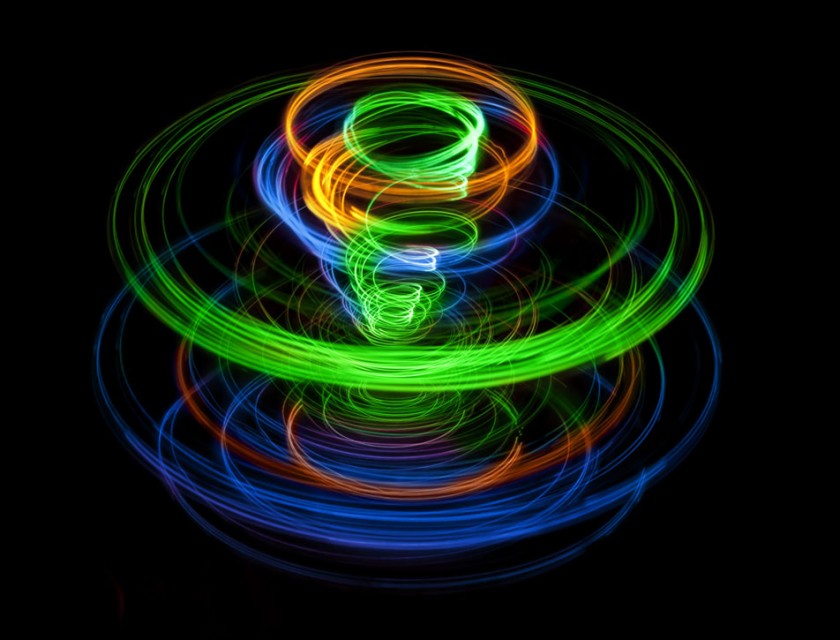

Naad-bindu, Dhyan-bindu, Amrit-nada and many other later Upanishads explain the unfolding of all creation and its names through Naad-Brahman and how a practitioner can attain ‘moksha’ or liberation. There is an outward evolution of sound from ‘eternal silence’ or anahat- naad[11] and then there is the involution through yoga and the chanting of ‘aum’.

In yoga, while doing the pranayama or ‘breath-training’, the first step is to plug one’s ears with the thumbs of both outstretched hands while placing the corresponding little fingers lightly on one’s nostrils – one can hear this ‘Universal-hum’ inside one’s head. This is the first step in meditation. The deep breathing that follows synchronizes the practitioner’s pranic life-force with the universal shakti or energy. The expansion of this universal energy through the individual mind into human expression is called pranav – which, interestingly, is another word for ‘aum’ in all Vedic literature. When the conch-shell or shankh is blown in Vedic rituals it is symbolic of this praṇav, for it is the individual praṇa that combines with the vayu or ‘breath’ to bring about the resonance.

- The concept of Naad is more than just sound. It actually includes the complete semiotic expression – ‘Sangitratnaakar’ says that “Naad is the very essence of all kinds of vocal & instrumental music and dance (nrittya)”. This is symbolized by the Nataraja form of Lord Shiva in which He is shown in the tandava-nrittya pose. Tandava is related to anger and the ‘opening of the third eye’ of Shiva . This dance form is very heavy on percussion and the damaroo in Shiva’s hand signifies the destructive rhythm of time or kaal.

Thus the conch-shell and the damaroo are both symbols of Naad. Whereas the former signifies creative energy, the latter stands for destructive forces. In short, Naad encompasses all universal vibrations – their evolution and dissolution.

Thus the conch-shell and the damaroo are both symbols of Naad. Whereas the former signifies creative energy, the latter stands for destructive forces. In short, Naad encompasses all universal vibrations – their evolution and dissolution.

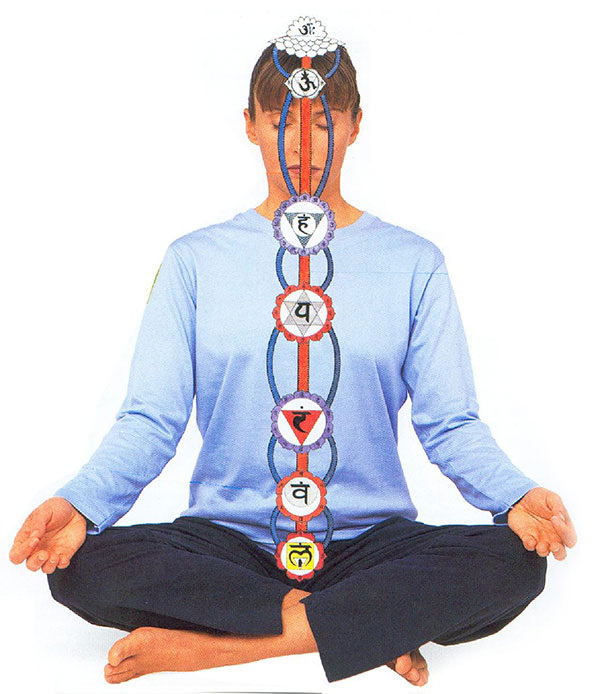

- In between these two limits, according to the Shiva- sutras , lies the ‘mother of all sounds’ – the matrika or the string of Sanskrit alphabets. These sounds are also distributed over the seven energy-centers or chakras of the human body and the kundalini-yoga describes how these various chakras can be excited by meditative chanting.

The ‘intent to act’ is called the samkalpa and is first felt in the mind as a thought, as an idea to do something. This latent desire is in the realm of anahat- naad and is also called the para-vaak or the region ‘beyond speech’. It is constructed out of our previous experience, the learned language, the symbolic memory and so on. The desire precipitates a need, a reason or a sense of purpose – this is called vikalpa . The mind observes, it searches for ways and means to crystallize this thought. This is the second layer of speech and it is called pashyanti. The next & third stage is madhyama, literally meaning ‘in-between’, where the life-force or prana lowers itself into the heart through 22 nervous paths called nadis. These 22 paths constitute the collection of shrutis and the heart is also the seat of the fourth chakra called the Anaahat-chakra for this reason. The breath or vayu rises from the navel or nabhi, the seat of the Manipura-chakra, in a ‘tight knot’[12] and combines with the prana in the hridaya or heart. Till now the sound is unbroken. As the vayu emerges from the throat, the Vishuddhi-chakra it finds distinction, delineation into the various components of speech and this fourth stage is called vaikhari. Till here the Shiva- sutras follow, a 5th century A.D. scholar, Bhartrihari’s sphota theory of language. The sutras however add the matrika as the fifth stage of speech synthesis. Now, let us look at the string of Sanskrit alphabets in detail.

■■ A single letter of the alphabet in Sanskrit is called akshara. In the Upanishads Brahman, the Unknown is also called akshara.[13] For, akshara has neither any substance nor does it possess any attributes. It is indestructible and undifferentiated. That which is dissoluble and melts away is called kshara and the opposite is a-kshara where the prefix ‘a’ denotes the negative. In other words akshara is to be first understood as the Imperishable, the constant in the universe, it is the Brahman and is the very pivot of this creation.

The word aksha also means the axle or the beam on which the cart’s wheel is balanced so akshara is T.S. Elliot’s ‘still point’, ‘the fixity’[14] about which all things rotate but it itself remains unmoved. This unbounded sphere ‘whose center is everywhere and the circumference nowhere’ finds an ego-centric limitation, an adjunct within the individual self. This human body is endowed with the organs of speech and here the meaning of akshara becomes the syllable – a small utterance. And this is ‘a’ ( A ) – the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet.

● Lord Krishna explains to Arjuna in the Gita 10.33 :-

I am the first letter ‘a’ among the akshara of the alphabet and am integral in the compounding of words in grammar. I am indestructible time. I am the Dispenser facing everywhere.

I am the first letter ‘a’ among the akshara of the alphabet and am integral in the compounding of words in grammar. I am indestructible time. I am the Dispenser facing everywhere.

The Sanskrit alphabet, unlike English, has the collection of vowels as a primary list called svars . The consonants are a secondary list and are called vyanjan . The svars are the ‘shining’ sounds and the vyanjan are the ‘reflected’ sounds. The first svar is ‘a’ and it is added to the end of every consonant. From there it integrates into every word and sentence. Thus ‘a’ ( A ) , the Brahman becomes “woven into the warp and woof of everything” in the words of Late Dr. S. Radhakrishnan. This structuring is unique to the Sanskrit language.

The Imperishable akshara seeds each letter of the alphabet and becomes manifold. These voiced syllables, structured into words and sentences, give rise to action. In the Gita an entire Section 8, titled ‘Akshara Brahma Yoga’ explains how our karma arises from thought and how thought arises from the multiplicity of the Akshara Brahma.

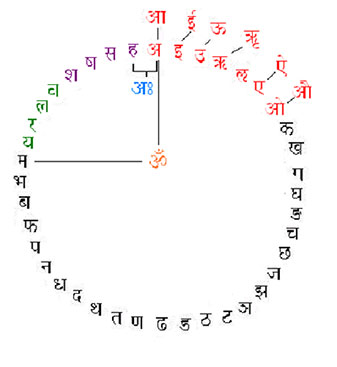

● The Siva Sutras of Abhinavagupata treat the multiplicity of the aksharas as the various shaktis of Lord Shiva . We have seen how Shiva is likened to the spanda or ‘a throbbing point’ also called a bindu . This Shiva – Shakti dichotomy gives rise to the string of alphabets called the Matrika-chakra , literally meaning the ‘Mother-wheel’. These are arranged in a circle or chakra much like the beads in a rosary and each letter has its individual universal resonant energy, a Divine Shakti .

The letters in red are the svars , the vowels. These are 13 in number and if ‘a’ ( A ), that stands for Brahman , the Unknown is suppressed we are left with 12 – the number of sun-signs. The vowels are like the day and they are the ‘shining ones’. They contribute the maatra or the meter and timing to the words and the mantras.

The letters in red are the svars , the vowels. These are 13 in number and if ‘a’ ( A ), that stands for Brahman , the Unknown is suppressed we are left with 12 – the number of sun-signs. The vowels are like the day and they are the ‘shining ones’. They contribute the maatra or the meter and timing to the words and the mantras.

The aksharas in black are the sparsh, the mute-consonants. These are the ‘dark ones’ and are 25 in number. Each letter e.g. the first ‘k’ needs the ‘a’ sound to complete it, for it is pronounced as ‘ka’. Therefore the mute-consonants have 26 syllables and this approximately is the number of waxing & waning cycles of the moon in a year.

The Divine reveals itself in serendipitous ways. There are many more symmetries embedded within this akshara-wheel that confirm this mysterious method.

- In terms of rigorous logic if Brahman, the Unknown manifests, it relegates Itself ! This epistemological problem is circumvented in Indian thought by introducing the concept of Ishvara. Where Brahman is the Absolute God, Ishvara reflects its power of Self-determination….this is best explained by using S. Radhakrishnan’s words [15]….

Brahman – Ishvara, here the first term indicates Infinite being and possibility, and the second suggests creative freedom. Why should the Absolute Brahman perfect, infinite, needing nothing, desiring nothing, move out into this world ? It is not compelled to do so. It may have this potentiality but it is not bound or compelled by it. It is free to move or not to move, to throw itself into forms or remain formless. If it indulges its power of creativity, it is because of its free choice.

In Ishvara we have the two elements of wisdom and power, Shiva and Shakti. By the latter the Supreme who is unmeasured and immeasurable becomes measured and defined. Immutable being becomes infinite fecundity.

Now, we have seen that ‘a’ ( A ) is akshara and similarly its manifestation Ishvara is the lengthened second vowel ‘i’ ( [- ) . Thus it can be understood as i-svara, literally meaning the ‘i’ ( [- ) vowel.

The Vedic equivalent of Ishvara is Lord Indra . The Aitareya Upanishad I .3.14 explains why Indra is so named. Idam means ‘this’ and ‘that which can be seen’ is idam adarsham. This is shortened to idaṁdra and further to Indra, a cryptic version ‘because the Gods like mysterious names’. In essence Indra like Ishvara is the perceivable projection of Brahman .

The Vedic equivalent of Ishvara is Lord Indra . The Aitareya Upanishad I .3.14 explains why Indra is so named. Idam means ‘this’ and ‘that which can be seen’ is idam adarsham. This is shortened to idaṁdra and further to Indra, a cryptic version ‘because the Gods like mysterious names’. In essence Indra like Ishvara is the perceivable projection of Brahman .

- ‘u’ is the unfolding maya, it is the measure of things as our consciousness molds out forms in the formless. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad shlöka I.3.23 says :-

And this ‘u’ is ‘udgitha’, the universal song. The vital breath ‘prana’ is ‘ut’, for by vital breath is this whole creation upheld, supported. The universal song, verily, is speech. This is ‘udgitha’, for it is ut and githa.

And this ‘u’ is ‘udgitha’, the universal song. The vital breath ‘prana’ is ‘ut’, for by vital breath is this whole creation upheld, supported. The universal song, verily, is speech. This is ‘udgitha’, for it is ut and githa.

The compilation of entire knowledge is the ‘universal song’, Gita. In its full form it should be called ‘udgitha’ . ‘Ud’ means ‘to evolve’ and ‘ut’ is the ‘life breath’ or prana ; coupled with speech this vital breath gives ‘name and form’ to all things in this conscious universe.

Ishvara is the eternal order. It can be sensed, yes, but yet it is strangely uniform, devoid of any dimensions of space, time and so forth. This is the samsara, the Sanskrit word for the world. Sam means ‘the same everywhere’. Sara means ‘the essence’. In this dimensionless world, the only disturbance, according to the Vedic Hymns of Creation, is a thought – “Let me be” – the Creator’s need to have a Self. This ‘thought’ disturbs the Uniformity, the Order, giving rise to the Chaos & Order dichotomy. The dimensions unfold and the Creator, Preserver & Destroyer trinity takes form.

Ishvara is the eternal order. It can be sensed, yes, but yet it is strangely uniform, devoid of any dimensions of space, time and so forth. This is the samsara, the Sanskrit word for the world. Sam means ‘the same everywhere’. Sara means ‘the essence’. In this dimensionless world, the only disturbance, according to the Vedic Hymns of Creation, is a thought – “Let me be” – the Creator’s need to have a Self. This ‘thought’ disturbs the Uniformity, the Order, giving rise to the Chaos & Order dichotomy. The dimensions unfold and the Creator, Preserver & Destroyer trinity takes form.

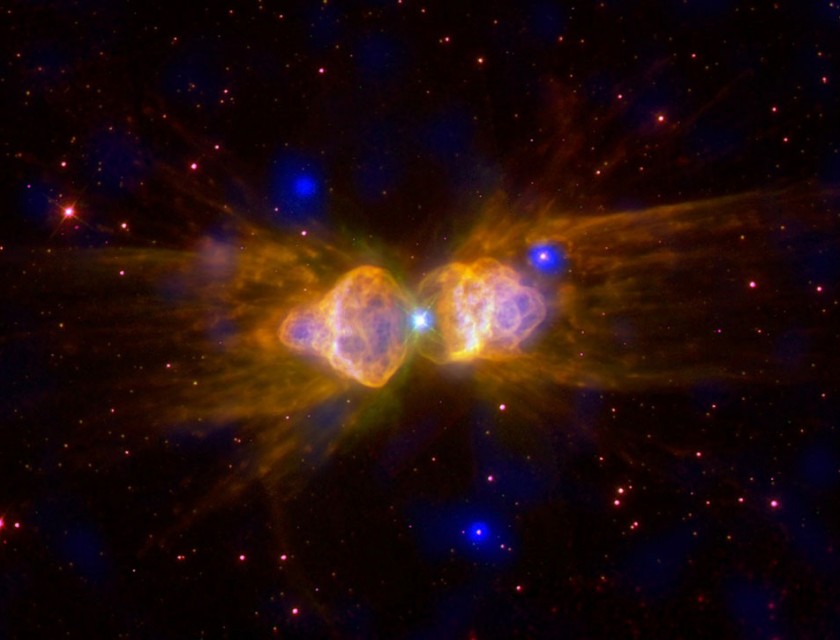

This trinity is variously explained in the texts but for our purpose here we consider Ishvara as the creative equanimity ; Shiva as the chaotic destroyer and Vishnu as the one that preserves order. In the galaxies above us the supernovas are bursting with tremendous energies and the black holes are coalescing these under crushing gravitational forces. These are the two extremes of the visible universe and beyond these all scientific explanations seize. The expanding supernovas is Vishnu that is always depicted with agni or fire emanating from it. The root verb ‘ag’ means ‘a tortuous movement’ and the suffix ‘ni’ means in this context ‘to throw out’. So, agni is ‘the flickering of the flame’ that shines and spews forth energy. The opposite is n-agni or nāgini that means a snake, literally ‘a black tortuous movement’ that absorbs energy.

Thus Shiva is portrayed with snakes around his neck. The river Ganges entangled in Shiva’s flowing mane, at another level, stands for ‘Aakash-Ganga’ – the Sanskrit name for our galaxy ‘the Milky-way’.

Shakti, power is the flow of energy between the Vishnu and Shiva back and forth.

-

-

- If we go back to the akshara-wheel , the last four letters in indigo viz. sh ( Sa ), shh ( Ya ), sa ( sa ) and ha ( h ) are called the Sibilants or ushma , meaning energy . They are the shakti symbols. The first three of these aksharas can be linked to the three Goddesses Shri Lakshmi, Usha and Saraswati…they represent the energies of the manifest universe. They are the mythological consorts of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma (Brahma is equivalent to Ishvara and is the perceivable deity of Brahman, the Unknown). In the Vedic sense energy is treated very differently from the western scientific method :-

Shri Lakshmi is the Goddess of wealth, worldly goods and material acquisitions. It is the favourite of the Hindu trading community. This stands for all transactions that move the count. That is what diminishes from one place increases at the receiving end. Let us say I give you money, it reduces with me but adds to your account.

Shri Lakshmi is the Goddess of wealth, worldly goods and material acquisitions. It is the favourite of the Hindu trading community. This stands for all transactions that move the count. That is what diminishes from one place increases at the receiving end. Let us say I give you money, it reduces with me but adds to your account.

- If we go back to the akshara-wheel , the last four letters in indigo viz. sh ( Sa ), shh ( Ya ), sa ( sa ) and ha ( h ) are called the Sibilants or ushma , meaning energy . They are the shakti symbols. The first three of these aksharas can be linked to the three Goddesses Shri Lakshmi, Usha and Saraswati…they represent the energies of the manifest universe. They are the mythological consorts of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma (Brahma is equivalent to Ishvara and is the perceivable deity of Brahman, the Unknown). In the Vedic sense energy is treated very differently from the western scientific method :-

-

Usha is that which keeps getting replenished. ….the rays of the sun ; the flowing rivers ; the sprouting leaves are all examples of this form of Shakti. The reservoir of energy is so huge that we get a feeling of ‘continuity’ in using it. Literally Usha means ‘the dawn’ and Rig Veda, the oldest of the Vedas, is replete with its praise.

Saraswati is the ‘energy that grows’ even though you part with it ! It is like the fruits of a tree that multiply or the dispersion of knowledge or like lighting many candles with one and so on. It is the mythical Goddess of speech and music. The root-verb for this type of increase is ‘brih’ and it is from this that the word Brahman is derived.

■■ The Siva Sutras of Abhinavagupata, cited above, explain the human form in terms of seven aksharas out of the Matrika-chakra . We will next look at these seven bija-mantras to try and understand how the divine symmetries are reflected in our body.

● The two aksharas , ‘a’ ( A ) and ‘h’ ( h ) are the first and the last letters of the alphabet respectively. The latter is the last of the Sibilants or the Shakti symbols. It is the aspirate and is uttered from the glottis or kantha ‘with an extra force of breath’. In terms of speech, its positioning in the glottis is adjacent to that of ‘a’ ( A ). Interestingly while the ‘a’ (A) sound is present in all the consonants, as discussed earlier, the ‘h’ ( h ) sound is present in half of the alphabet (barring the nasal stops). For example to the ‘ka’ ( k ) sound the aspirate is added to bring about the next letter ‘kha’ (K ). The former is called the alp-prana or ‘lesser life breath’ and the latter is called maha-praṇa or ‘larger life breath’.

The shlöka II.3.6 of Aitareya Ārāṇyaka explains this :- … ‘a’ is the whole of speech and being manifested through the mutes and the sibilants it becomes manifold and various. If uttered in a whisper it is this prāṇa, if forcefully, that body – sharira. Therefore it is hidden, as hidden as the previous body encapsulated in this prāṇa . But spoken forcefully it is that body and visible, for body is visible. Now ‘a’ ( A ) is the immutable, the symbolic Unknown – if this is the whisper, then as we force the breath just a little, what we get is the aspirate sound ‘ah’ ( A: ) .

Now ‘a’ ( A ) is the immutable, the symbolic Unknown – if this is the whisper, then as we force the breath just a little, what we get is the aspirate sound ‘ah’ ( A: ) .  It is both ‘a’ and ‘h’ combined. This is called the visarga sound. As shown in the akshara-wheel , at the top, the visarga is not included in the main alphabet and hence it is termed ayogavāḥ or ‘that which is not part of the harness’. The visarga is the bija-mantra for the Sahasarara or the Crown-chakra . Here we see that another level of symmetry emerges – ‘ah’ ( A: ) closes the circle pictorially – signifying the internal/external division of the body or atma. The individual ‘I’ has thus taken form and this is called ‘aham’ ( AhM ). It is the ‘ah’ ( A: ) sound with the Shiva bindu on top of it. Thus there is an inside and there is an outside – with the language of consciousness as the dividing membrane!

It is both ‘a’ and ‘h’ combined. This is called the visarga sound. As shown in the akshara-wheel , at the top, the visarga is not included in the main alphabet and hence it is termed ayogavāḥ or ‘that which is not part of the harness’. The visarga is the bija-mantra for the Sahasarara or the Crown-chakra . Here we see that another level of symmetry emerges – ‘ah’ ( A: ) closes the circle pictorially – signifying the internal/external division of the body or atma. The individual ‘I’ has thus taken form and this is called ‘aham’ ( AhM ). It is the ‘ah’ ( A: ) sound with the Shiva bindu on top of it. Thus there is an inside and there is an outside – with the language of consciousness as the dividing membrane!

The aspirate ‘h’ ( h ) sound is representative of the sharira or the body, as explained in the shlöka above. This is the bija-mantra for the Throat-chakra.

-

-

-

- Paṇini, the oldest Indian grammarian who wrote his famous Asthadhyayi few centuries before Christ, has explained a system of pratyahara or abbreviation in which the first and the last letter actually include the entire list between them. In this light ‘ah’ ( A: ) can be understood as the pratyahara for the entire alphabet .

From the sound of ‘a’ ( A ) , the first letter to the sound of ‘m’ ( ma ) , the last letter of the mute-consonants the entire organ of speech is traced. The pronunciation travels from the glottis i.e. the guttural, along the palate to the cerebral region, from there to the dental and finally ends at the lips or the labial region. Thus the entire mouth cavity is structured within this part of the alphabet and from here the symmetry gets reflected into the entire discursive language. Now, the mantra ‘aum’ ( ! ) can be understood as the pratyahara for all these vowels plus all the mute-consonant sounds and hence the complete definition of the vocal apparatus starting from the glottis to the lips. This is the Universal mantra for the liberation of the senses and during meditation helps in suppressing the complete cacophony of thoughts and hence silencing the mind. This is the bija-mantra for the Ajna-chakra located at the center of the forehead where the ceremonious tika is put during Indian rituals.

From the sound of ‘a’ ( A ) , the first letter to the sound of ‘m’ ( ma ) , the last letter of the mute-consonants the entire organ of speech is traced. The pronunciation travels from the glottis i.e. the guttural, along the palate to the cerebral region, from there to the dental and finally ends at the lips or the labial region. Thus the entire mouth cavity is structured within this part of the alphabet and from here the symmetry gets reflected into the entire discursive language. Now, the mantra ‘aum’ ( ! ) can be understood as the pratyahara for all these vowels plus all the mute-consonant sounds and hence the complete definition of the vocal apparatus starting from the glottis to the lips. This is the Universal mantra for the liberation of the senses and during meditation helps in suppressing the complete cacophony of thoughts and hence silencing the mind. This is the bija-mantra for the Ajna-chakra located at the center of the forehead where the ceremonious tika is put during Indian rituals.

- Paṇini, the oldest Indian grammarian who wrote his famous Asthadhyayi few centuries before Christ, has explained a system of pratyahara or abbreviation in which the first and the last letter actually include the entire list between them. In this light ‘ah’ ( A: ) can be understood as the pratyahara for the entire alphabet .

-

-

-

-

-

- There are four aksharas, shown in green in the akshara-wheel viz. ‘ya’ ( ya ), ‘ra’ ( r ), ‘la’ ( la ) & ‘va’ ( va ). These are dual combinations of vowels and are called the Semi-vowels or antahstha. These antahstha are so called because they are in-between the vowels and the mute consonants. However, the prefix antar means both ‘intermediate’ as well as ‘internal’. Thus they reflect the inner or ‘returning’ energies of the body or sharira. These four aksharas are the bija-mantra of the lowest four of the seven chakras according to the Shiva-sutras.

-

-

‘a’ ( A ) combines phonetically with the second pure vowel ‘i’ ( [ ) to give ( [+A) – ‘ya’ ( ya ) and this is the bija-mantra for the Heart or Anahata chakra. This signifies the reflection of the Ishvara and the Unknown in the hridaya or the human heart.

Similarly ‘a’ ( A ) combines phonetically with the fourth pure vowel ‘ri’ ( ? ) to give ( ?+A) – ‘ra’ ( r ) and this is the bija-mantra for the Navel or Manipur chakra. Ritah is the word for ‘order’ and it is through the navel that the umbilical cord introduces prana into the human body.

In the same manner‘a’ ( A ) combines phonetically with the third & fifth pure vowels ‘u’ ( ] ) & ‘lri’ ( ; ) respectively to give ( ]+A) – ‘va’ ( va ) and ( ;+A) – ‘la’ ( la ) these are the bija-mantras for the lowest two charkas – ‘la’ for the Genitals and ‘va’ for the Faecal position. These are called the Swadishthan & Muladhar chakras respectively. These four aksharas are also called the yam ( yama\ ) symbols. And this is the name of Lord of Death in the Vedas thus it signifies time-bound decaying of energies. Interestingly, if we look at the akshara-wheel ( ma ) and ( ya ) are contiguous. If we go clockwise ‘yam’ ( yama\ ) could be the pratyahara for the entire alphabet signifying its closure or death. On the other hand if we go anti-clockwise from ( ma ) to ( ya ) and add an extra matra or meter to each syllable for extension in time – we get the unfolding of maya !

These four aksharas are also called the yam ( yama\ ) symbols. And this is the name of Lord of Death in the Vedas thus it signifies time-bound decaying of energies. Interestingly, if we look at the akshara-wheel ( ma ) and ( ya ) are contiguous. If we go clockwise ‘yam’ ( yama\ ) could be the pratyahara for the entire alphabet signifying its closure or death. On the other hand if we go anti-clockwise from ( ma ) to ( ya ) and add an extra matra or meter to each syllable for extension in time – we get the unfolding of maya !

■■ Involution is the path of looking within ourselves. It is the path of meditation and yoga. And a very important role, in this entire process, is played by the mantras – a string of words well-knitted to enhance this inward journey. We went through four stages of evolution of speech in reaching matrika – the exposition of words and language. To summarize, these were, para-vaak, pashyanti, madhayma and vaikhari. Similarly there are four mantras to assimilate the returning energies of the sadhak or practitioner.

The first mantra, according to the Shiva- sutras, is ‘hamsa’. This mantra brings about the awareness of breathing. For, ‘ha’ is samhara-bija or the mystic letter denoting inspiration of breath and ‘sa’ is the shrishti-bija or the mystic letter denoting expiration. These sounds just happen as we inhale and exhale 21,600 times approximately everyday and the concentration on this fact enhances deep-breathing or pranayama. Incidentally, the word ‘hamsa’ is also the name of the mythical white, swan-like bird which is very rarely seen and in folk-lore the flying away of this bird is likened to the release of prana at the time of death. These are the white swans on Goddess Saraswati’s sides.

The second mantra is ‘soham’. Here the sequence of awareness is reversed – the ‘sa’ syllable for exhaling comes before the ‘ha’ syllable for inhaling. This mantra, therefore, starts the sadhak on his inward journey and at the same time makes him aware of his deeper self. For, ‘aham’ means self and this mantra should be understood as ‘sa-aham’ being chanted rapidly.

The third mantra envelopes the second and adds the sound of the presiding deity Lord Shiva. Thus it is ‘Shivoham-shivoham’ and it is chanted in unison with the ‘in’ and ‘out’ breathing. The sadhak rises above the multiplicity of the external reality and begins to merge with the dichotomy of the self and Shiva. Note that the sound of ‘aum’ is already ensconced in this and the previous mantra. For, ‘aum’ is the last mantra. It is the bija sound for the ‘third-eye’ or the Ajna-chakra. We have seen it is the abbreviation of the entire Sanskrit vowels and mute consonants from ‘a’ to ‘ma’ . Its annunciation traces the entire organ of speech from the glottis to the lips or the labial region. When chanted it resonates sonorously in the cranial cavity urging the sadhak back towards the realm of para-vaak or the Unknown Naad-Brahman.

For, ‘aum’ is the last mantra. It is the bija sound for the ‘third-eye’ or the Ajna-chakra. We have seen it is the abbreviation of the entire Sanskrit vowels and mute consonants from ‘a’ to ‘ma’ . Its annunciation traces the entire organ of speech from the glottis to the lips or the labial region. When chanted it resonates sonorously in the cranial cavity urging the sadhak back towards the realm of para-vaak or the Unknown Naad-Brahman.

As a word of caution, this is not as simple as it sounds. It requires proper instruction from a Guru, the correct yogic positions and austerities, and a tremendous will power to take on this initiation.

Conclusion

This then is the circle of Divine sound in Hindu thought. We have journeyed from the mind of the enlightened rishi that was home to shruti – the first inspired thought. This thought precipitated as shabd, the first word and then into the multiplicity of the shlokas. Then came the speech or vaak, the rhythm and chhands that together gave birth to the sargam or music. All this combined in the Divine song or vaani.

We then reached the larger, more metaphysical concept of all sounds as Naad-Brahman and how it unfolds from Naad-bindu into all vocal and semiotic forms.

Next, we studied the matrika-chakra and learnt how the Divine and the akshara are intertwined. The Creation, the language, the human life processes are all part of One large symmetry. The Sanskrit alphabet reflects this symmetry in an amazingly profound manner leading to root verbs, its meters and other structures giving one the feeling of many more layers of meaning.

Subsequently, we looked at the seven chakras of the human body and their respective bija-mantras or ‘seed-sounds’.

And at the end, the returning path to coalesce all this drama back into the Unknown – sans speech, sans music, sans sound, sans everything . Just ‘aum’ the Universal mantra – the final merger.