Māyā

Māyā [1] is derived from the root √ma : means – to measure, to form, to limit . In the Vedāntic tradition it means specifically , “the illusion superimposed upon reality as an effect of ignorance.” Later Śankara describes the entire visible cosmos as māyā, an illusion superimposed upon true being by man’s deceitful senses & unilluminated mind [3].

- The Nirukta [4] (2.8) first relates the root √ma to mātā which means “the atmosphere” encircling the earth. This also means the “mother’s womb” in it the ātmā : soul takes shape and form and is born in this world. The womb ensconces the ātmâ : self. Similarly the atmosphere covers the earth. Literally, therefore, mātā means “ a vast region encompassed by air” and the mother’s womb is the soul’s passage into this world of māyā . Here it is nurtured, develops into a fœtus and takes on the human shape and size – ready for its earthy experiences.

- What is this māyānvi world that the soul now enters ? – the answer is best given by excerpting from Heinrich Zimmer [5] :-

Māyā is the measuring out, or creation, or display of forms; māyā is any illusion, trick, artifice, deceit, jugglery, sorcery, or work of witch-craft; an illusory image or apparition, phantasm, deception of the sight….The māyā of the Gods is their power to assume diverse shapes by displaying at will various aspects of their subtle essence. But the Gods are themselves the productions of a greater Māyā : the spontaneous self-transformation of an originally undifferentiated, all-generating divine Substance. And this greater Māyā produces, not the Gods alone, but the Universe in which they operate. All the Universes co-existing in space and succeeding each other in time, the planes of being and the creatures of those planes whether natural or supernatural, are manifestations from an inexhaustible, original and eternal well of being, and are manifest by a play of māyā. In the period of non-manifestation, the interlude of the cosmic night, māyā ceases to operate and the display dissolves.

Māyā is existence: both the world of which we are aware, and ourselves who are contained in the growing and dissolving environment, growing and dissolving in our turn. At the same time, Māyā is the supreme power that generates and animates the display: the dynamic aspect of the universal Substance. Thus it is at once, effect (the cosmic flux), and cause (the creative Power). In the latter regard it is known as Shakti, “Cosmic Energy”…..

Having mothered the Universe and the individual (macro- and microcosm) as correlative manifestations of the Divine, Māyā then immediately muffles consciousness within the wrappings of her perishable production. The ego is entrapped in a web, a queer cocoon. “All this around me,” and “my own existence”– experience without and experience within– are the warp and woof of the subtle fabric. Enthralled by ourselves and the effects of our environment, regarding the bafflements of Māyā as utterly real, we endure an endless ordeal of blandishment, desire and death; whereas, from a standpoint just beyond our ken Māyā – the world, the life, the ego, to which we cling– is as fugitive and evanescent as cloud and mist [6]……

- In S. Radhakrishnan’s [7] thought māyā has great preponderance. In the Introduction to his Principal Upanishads he says :-

The actual fabric of the world, with its loves and hates, with its wars and battles, with its jealousies and competitions as well as its unasked helpfulness, sustained intellectual effort, intense moral struggle seems to be no more than an unsubstantive dream, a phantasmagoria dancing on the fabric of pure being… Indifference to the world is not, however, the main features of spiritual consciousness…The withdrawal from the world is not the conclusive end of the spiritual quest, There is a return to the world accompanied by a persistent refusal to take the world as it confronts us as final…

In the Maitrī Upanishad, the Absolute is compared to a spark, which, made to revolve, creates apparently a fiery circle,….The Aitareya Upanishad asserts that the universe is founded in consciousness and guided by it, it assumes the reality of the universe and not merely its apparent existence. To seek the one is not to deny the many…. māyā in this view states the fact that Brahman without losing his integrity is the basis of the world. Questions of temporal beginning and growth are subordinate to this relation of ground and consequent. The world does not carry its own meaning. To regard it as final and ultimate is an act of ignorance…In the Chāndogya Upanishad (III.14), Brahman is defined as tajjalān as that (tat) which gives rise to (ja), absorbs (li) and sustains (an) the world. The Brhad-āranyaka Upanishad (V.5.1) argues that satyam consists of three syllables, sa , ti , yam , the first and the last being real and the second unreal, madhyato anrtam. The fleeting is enclosed on both sides by an eternity which is real….

The different metaphors are used to indicate how the universe rises from its central root, how the emanation takes place with the Brahman remains ever-complete, undiminished. ’As a spider sends forth and draws in (its thread), as herbs grow on the earth, as the hair (grows) on the head and the body of a living person, so from the Imperishable arises the universe. Again, ‘As from a blazing fire sparks of like form issue forth by the thousands even so, many kinds of beings issue forth from the Immutable and they return thither too.’ The many are parts of the Brahman even as the waves are parts of the sea…

Indra is declared to have assumed many shapes by his māyā. Māyā is the power of Īśwara from which the world arises…it is Īśwara who has the power of manifestation and māyā is that which measures out, moulds forms in the formless….Brahman is logically superior to Īśwara who has the power of manifestation….The Beyond is not an annulling or a cancellation of the world of becoming, but its transfiguration. The Absolute is the life of this life, the truth of this truth….While the world is created by the power of māyā of Īśwara, the individual soul is bound down by it in the sense of avidyā or ignorance. We are subject to this delusion when we look upon the multiplicity of objects and egos as final and fundamental. Such a view falsifies the truth. It is the illusion of ignorance…while the world process reveals certain possibilities of the Real, it also conceals the full nature of the Real.

- A book by Donald A. Braue titled “ Māyā” – In Radhakrishnan’s thought …is a must-read for every serious student of this subject. Here there is an elaborate discussion on ‘Six Meanings Other Than Illusion’ for the word māyā in Radhakrishnan’s writings :-

- māyā1 : as inexplicable mystery : Radhakrishnan is convinced that reality in its entirety cannot be grasped by the discursive intellect. This conviction shapes the first meaning of māyā. Most often, māyā1 signifies the inexplicable mystery surrounding the relation between Brahman and the world….

We can never understand how the ultimate Reality is related to the world of plurality. Since the two are heterogeneous, and every attempt at explanation is bound to fail. This incomprehensibility is brought out by the term māyā1. When the Absolute is taken as pure being, its relation to the world is inexplicable anivārcanīya.

We know that without the background of being, there can be no world…The real is one, yet we have two…As to how the primal reality in which the divine light (Īśwara) shines everlastingly can yet be the source and fount of all empirical being, we can only say it is a mystery, māyā 1….

The most modest course for philosophers would be to admit a mystery at the center of things. Ko ved…kuth iyam visriśtī : who knows whence this creation is born ? It is a mystery we cannot penetrate and a wise agnosticism is the only rational attitude.

- māyā2 : as Power of Self – Becoming : As the power of self-becoming māyā2 is that which measures out, molding forms in the formless. Māyā2 is closely related to theories of creation. Whereas māyā1 is an epistemological concept, māyā2 is a cosmogonic concept. It refers to the creative activity which R. identifies as poise two of reality – Īśwara…..”The power of self-becoming” is R’s translation of ātmavibhūti , a compound of ātman and √bhū plus vi. Ātman cannot be translated into English adequately, but it is often rendered self. Monier Williams says the prefix vi plus the verbal root bhū in the Rg Veda means “to arise, be developed or manifested, expand, appear.” Therefore, ātmavibhūti means “the arising, developing, manifesting, expanding or appearing of the self “….

Theoretical philosophy, interested in deducing the world of being from the first principle of an Absolute self which has nothing contingent about it, is obliged, whether in East or West , to accept some principle of self-expression (māyā ), of objectivity…. The self limitation of the primal consciousness, or the rise of the obstacle against which the self breaks itself, has to be assumed, however incomprehensible it may be….

It is important to notice that R. thinks this power of self-expression is a sine qua non of the Absolute. There is a well known song which children sing : “My hat, it has three corners; three corners has my hat. And had it not three corners, it would not be my hat.”…

This power of actualization is given the name of māyā in later Vedānta, for the manifestation does not disturb the unity and integrity of the One. The one becomes manifested by its own intrinsic power, by its tapas….The Śvetāśvatara Upanisad describes God as māyin, the divine art or power by which the divinity makes a likeness of the eternal prototypes or ideas inherent in his nature…

- māyā3 : as Duality of Consciousness and Matter : Māyā1 as inexplicable mystery is an epistemological concept and māyā2 as power of self-becoming is a cosmogonic concept. Māyā3 as duality of consciousness (purusa) and matter (prakrti) is a “uniting” concept. R. uses māyā3 to unite Sāmkhya and Vedānta darśanas. He incorporates the Sāmkhya categories of consciousness (purusa) and matter (prakrti) into his own system….This calls attention to R.’s view that twoness or duality of consciousness and matter, being and non-being , is inherent in all things. Purusottama is Īśwara, poise two of reality. R. thinks even Īśwara’s nature is dual. He remarks that “All things partake of the duality of being and non-being from Purusottama downwards”. R. holds that the world process is dual : a mixture of self and not-self, spirit and nature, consciousness and matter…sat and asat. In short hirānyagarbh (poise three) and Virāt (poise four) express symbolically this duality which is inherent in all beings and even Īśwara. All things in the Universe are comprised of consciousness and matter to some degree…

Māyā3 is like an ellipse. An ellipse is the locus of all points the sum of whose distances from two fixed points is equal. Usually oval, an ellipse can be drawn by tying a string loosely between two nails, by pulling the string taut with a pencil point, and by swinging the pencil all the way around the two nails. These two nails in this simile are consciousness and matter. All things in the Universe lie somewhere on the ellipse itself. Māyā3 signifies this duality inherent in all things.

- māyā4 : as Primal Matter : māyā4 also unites Sāmkhya and Vedānta philosophies. For R. , the phrase “primal matter” is identical with the phrases “lower prakrti” and “unmanifested prakrti”.

Māyā4 as primal matter, in R.’s view, is that from which all existence arises. He theorizes that “Māyā is also used for prakrti, the objective principle which the personal God uses for creation”….The world is traced to the development of prakrti which is also called māyā in the Advaita Vedānta, bu this prakrti or māyā is not independent of spirit. It is dependent on Brahman….

The Absolute breaks up its wholeness and develops the reality of self and not-self. The self is God, and the not-self the matter of the Universe. All Hindu systems of philosophy posit these two ultimate principles. In the Samkhya it is purusha and prakrti ; in the Vedānta it is Īśwara and māyā ; in Vaishnavism it is Krishna and Radhā ; and in Shaivism it is Shiva and Shaktī. Māyā, Radhā and Shaktī are respectively the intellectual, the emotional and the volitional aspects of the same thing viz. prakrti. Krishna, Shiva and Īśwara too are one in essence.

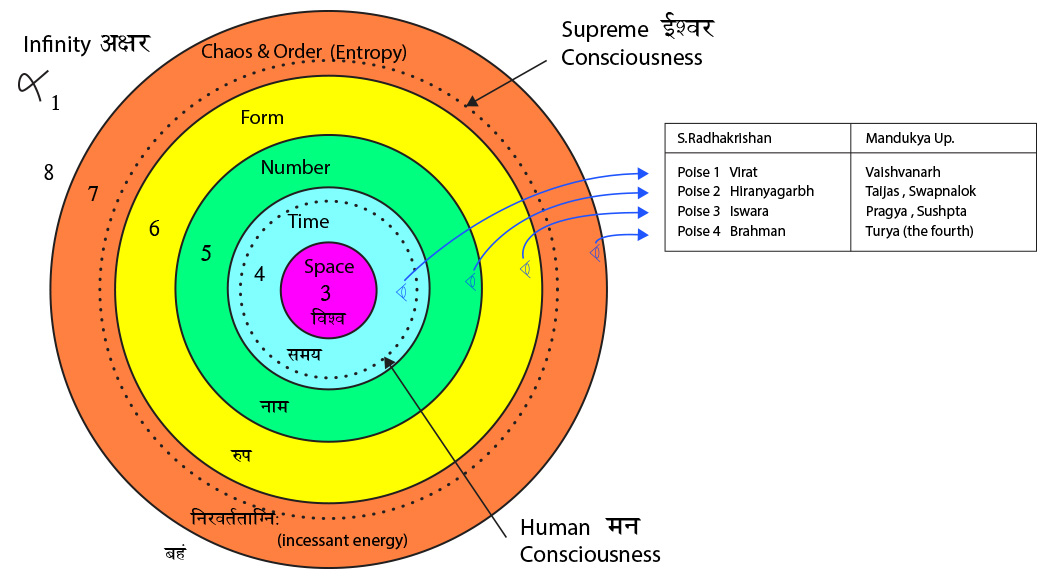

At this point I would like to introduce the reader to the Vedic concept of Dimensions (Table 1 – Maya_Dimensions). This will be further developed in later chapters, however, the four poises given by R. fit in well with this picture. There does appear to be some confusion in the terminology in various texts and considering the verbal to written changes of this knowledge over the millennia minor distortions are bound to happen. The OBSERVER is shown as “Four Eyes” at four levels of our Consciousness. The higher dimensions unfold in this Consciousness as the “Four Poises” or as the Mind, Id, Ego and Super-ego.(The full size picture can be viewed by clicking on Table 1…..)

- māyā5 : as Concealment : Sir R. feels that the phenomenal things conceal “something more” which is behind them. He contends that our logical inquiry into the nature of reality is blocked because the manifested world hides the unity and harmony of the whole.

As the manifested world hides the real from the vision of mortals, it is said to be delusive in character. The world is not an illusion, though by regarding it as a mere mechanical determination of nature unrelated to God, we fail to perceive its Divine essence. It then becomes a source of delusion……God seems to be enveloped in the immense cloak of māyā. R. depicts the world as a source of delusion, not an illusion [8]. The world deludes, he generalizes, when the perceiver fails to perceive it as it really is – related to God. The implication is that the problem of māyā is inherent in the attitude of those who perceive, not in that which is perceived……The term illusion is generic; the term delusion is specific.

First of all, R. regards māyā5 as “the beginning-less cosmic principle which hides reality from the vision of man.” He believes liberation (moksa) from the endless rebirth (samsāra) requires a vision of the real…..Māyā evolves a variety of names and forms, which in their totality is the universal movement (jagat). It also, conceals the eternal Brahman under this aggregate of names and forms. Māyā has the two functions of concealment of the real and the projection of the unreal. The world of variety screens us from the real.

Some think Creation’s meant to show him forth,

I say it’s meant to hide him all it can.

Browning, “Bishop Blougram’s Apology”

- modifies the concealment (or veil) metaphor for māyā as both the veil and dress of God. A dress serves two purposes – it hides and it displays. Likewise māyā5 can be likened to a scrim (A thin canvas used in theater and opera in order both to show the audience shapes and colors and to hide what is going on backstage)…..The view which regards the multiplicity as ultimate is deceptive (māyā) , for it causes the desire to live separate and independent lives. When we are completely separate entities, sharing little and mistaking individuality, which is one of the conditions of our life in space-time, for isolation and not wishing to lose the hard outlines of our separate existence. Māyā keeps us busy with the world of succession and finitude.

So long as the individual thinks himself to be a separate atom in this immense universe, so long as he has the idea that he is the chief actor in the stage, he is in the world of māyā,…. When we recognize the essence of the finite to be in the Infinite, when we realize that we are but instruments of a nobler purpose, we get out of the world of māyā.

Borrowing a root image from Western thought , R. diagnoses the people in Plato’s cave [9] as suffering from the persistent and false belief that the shadows are real objects…..The simile of the cave reminds us of the Hindu doctrine of māyā, or appearance. Plato compares the human race to men sitting in a cave, bound, with their backs to the light and fancying that the shadows on the wall before them are not shadows but real objects.

- wants people to expand their partial consciousness by ‘seeing’ both the forms and the formless. In particularly he says ”the world is not a deception but the occasion for it”….Just as a desert “puddle” can be dangerous if the truth about it is not known, so also R. thinks māyā5 can be dangerous if we do not pierce its veil.

How to go beyond this concealment or veil is the next attempt of R.’s dissertation :-

For R. a distortion of vision is also a distortion of values….When the Hindu thinkers ask us to free ourselves from māyā , they are asking us to shake off our bondage to the unreal values and ignorance which are dominating us. They do not ask us to treat life as an illusion or to be indifferent to the world’s welfare…..When the illusion of the mirage is dissipated by scientific knowledge, the illusory appearance remains, though it no longer deceives us. We see the same appearance but give a different value to it….

The world has the tendency to delude us into thinking that it is all, that is self-dependent, and this delusive character of the world is also designated māyā in the sense of ignorance (avidyā). When we are asked to overcome māyā, it is an injunction to avoid worldliness. Let us not put our trust in the things of the world. Māyā is concerned not with the factuality of the world but the way in which we look at it…….While māyā covers the whole cosmic manifestation avidyā relates to the ignorance of the individual…..When we look at the problem from the objective side, we speak of māyā, and when from the subjective side, we speak of avidyā. Even as Brahman and Ātman are one, so are māyā and avidyā one. The tendency for the human mind to see what is really one as if it were many, is avidyā ; but this is common to all individuals…….The ignorance (avidyā) that concerns R. is the lack of spiritual wisdom and not the lack of intellectual sophistry.

- māyā6 : as One–side Dependence : While the world is dependent on Brahman. the latter is not dependent on the world. This one-sided dependence and the logical inconceivability of the relation between the Ultimate Reality and the world are brought out by the word māyā.

The one-sided dependence of the world on the Absolute is illustrated by Samkara by his rope and the snake example elaborating the difference between appearance (vivarta) and transformation (parināma)……we have the latter when milk is changed into curds. and the former when the rope appears as the snake. The different illustrations used by Samkara of the rope and the snake, the shell and the silver, the desert and the mirage, are intended to indicate this one-sided dependence of the effect on the cause and the maintenance of the integrity of the cause. In the case of transformation, the cause and the effect belong to the same order of reality, while in that of appearance the effect is of a different order of being from the cause…..

The doctrine of māyā declares that the world is dependent on and derived from the Ultimate Reality. It has the character of perpetual passing away, while the real is exempt from change. It has therefore a lower status than the Supreme itself. In no case is its existence to be confused with illusory being or non-existence.

The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven’s light forever shines. Earth’s shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-colored glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.– Die,

If thou wouldst be with that which thou dost seek !

Follow where all is fled ! – Rome’s azure sky ,

Flowers, ruins, statues, music, words, are weak

The glory they transfuse with fitting truth to speak.

P.B.Shelley, “ L II , ADONAIS”

Māyā in this view states the fact that Brahman without losing his integrity is the basis of the world. Though devoid of all specifications, Brahman is the root cause of the Universe. ‘If a thing cannot subsist apart from the something else, the latter is the essence of that thing.’ R. judges that the discursive intellect cannot grasp in its entirety the content of this cause and affect dichotomy since there is “something more”. This phrase cannot be caught in the net of words we can refer to it paradoxically as changeless. that grows and bursts forth, unity and continuity, consciousness, the whole, harmony and truth. Questions of a temporal beginning are subordinate to this relation of ground and consequent. The world does not carry its own meaning. To regard it as final and ultimate is an act of ignorance. [10]

Two important distinctions emerge from Radhakrishnan’s extensive writings extracted above. Firstly māyā is not the illusionary world around us as is commonly interpreted. This world is an illusion per se because our consciousness cannot simply penetrate the veil cloaking Brahman. To be able to do so our minds need to overcome their ignorance (avidyā). The process of collecting this knowledge (vidyā) painstakingly is the path to be taken by the souls seeking enlightenment and the final goal of nirvāna. The delusion that strays us from this process of seeking life’s truth, its natural rhythm, its harmony is māyā. The rising sun, the moving earth and planets, the changing seasons, the blue sky, the swaying trees, the chirping birds…all these are illusionary to our senses that mistakenly compartmentalize this vast sea of universal energy flow into distinctive experiences. To help the mind rise above this diversity that is continuously being fed in by our senses we need to develop a deeper perspicacity. The path to this higher goal of knowledge or “something more” (as R. puts it) is through the rhythmic process happening around us even though it is illusionary to our senses. We should not get deluded by this and continue our Karmic search with minimum perturbation. This is the path to spiritual wonders described, time and again in their various ways, by the Great men who have truly reached enlightenment.

This cloak of Brahman is the vāsyam referred to in the first line of the first shlöka of Īśavāsyopniśad :-

īśāvāsyam idam sarvam yat kim ca jagatyām jagat…

All this, whatsoever moves in this Universe, including the Universe itself moving, is indwelt or pervaded or enveloped or clothed by the Lord….[11]

Chinmayananda says – “vāsyam is a pregnant word in Sanskrit with unlimited suggestiveness and innumerable meanings. The root ‘vas’ means ‘clothing’, ‘covering’, ‘inhabiting’, ‘enveloping’, or ‘pervading’. And here in the context all these meanings are applicable. The Great Rishī exclaims that ‘all this’ (īdam sarvam) that we are perceiving through our sense-organs or by the intervention of our mind and intellect –all this – is indwelt by the Spirit which is the Lord of the world-of-perception……

All this should be covered (clothed) by the Lord (Īśa). The world-of-matter acts as the veil, covering from our vision the Divinity within, and therefore, we are unable to perceive the Divine presence everywhere around us in the without. The Light of consciousness illumines all our perceptions, feelings and thoughts. It illumines our sense-organs, mind and intellect. It pervades all and nothing pervades it. And yet, the paradox is the world-of-plurality covers so successfully the vision of Truth, in whose light alone the plurality can be experienced.”

The second distinction that emerges in R.’s writings is the One-sided Dependence of the world on Brahman. Whereas the latter is eternally tranquil, this world is subject to incessant vibrations (jagatyām jagat). The emergence of our consciousness into this picture gives rise to the duality of appearance (vivarta) and transformation (parināma). The Īśwara is a transformation of the Brahman, a process which is extraneous to the consciousness and captures all the vividness of Brahman without diminishing its order whereas appearance is a reflection of the external reality into the sensuous mirror that is us – the Observer. Now this convergence entails a loss of information for it is restricting the Īśwara and its immensity to the limit of our collective neural combinations. This appearance is of an order lower than the cause from which all this grows, the Brahman. In the external reality, at our hand, this results in a chirality, an arrow of time, a single sided energy flow.

In the Yajur Veda (14.18) mā as measure is interestingly detailed at three levels viz. mā (maa) , pramā (p`maa) and pratima (p`itmaa). The further explanation to this shlöka is given in Śatapatha Brāhmana VIII.3.3.5 [12]. Here, I feel, is an important metaphysical concept which should be studied meticulously. Let us commence with Max Müller’s translation[13] :-

‘The metre Measure;’ – the measure mā, doubtless , is this terrestrial world ayam vai lökö mā ; for this world is, as it were measured ayam hi lökö mita iva; – ‘the metre Fore-measure !’ – the fore-measure pramā , doubtless, is the air-world itya antarikś lökö vai , for the air-world is , as it were, measured forward from this world pramā antarikśa lökö hyasmāt lökāh pramita iva ; – ‘the metre Counter-measure,’ – the counter-measure pratimā , doubtless, is yonder heavenly world itya asau vai lökah pratimā , for yonder-world is, as it were, counter-measured in the air aiśa hya antrikśa löke pratimita iva ;……

counter-measured is explained in a note as ‘That is, made a counterfeit, or copy, of the earth.’

The first level of mā , metre-measure is bhūlök , the world at hand, the terrestrial surroundings – the prithvī . The second level of pramā , fore-measure is that which is beyond our reach and this is the antarikś which is usually translated as the sky or atmosphere. However, this word should not be restricted to the upper reaches only. I feel antarikś extends to both sides of the spectrum – the very large or the very small. The third level is the pratimā , Max Müller translates it as the counter-measure but actually this is the dyauh , as is explained in S. Br. VIII.3.3.5. and Y.V. 14.19. it should be understood as the edge of the universe, but again on both ends of the scale the extremely large….the galaxies, the quasars or the extremely minute the quarks, the neutrinos and so on and so forth. dyauh we can study only by indirect means, by imagery or reflection and this is exactly what pratimā stands for.[14]

Analytically, therefore, māyā can be understood to unfold at three levels that essentially encompasses the entire scale of sizes which the human mind can derive in its consciousness. The mā lends itself to direct experience and can be subjected to measure by hand. This is restricted to the prithvī or the earthly-domain. The pramā is just out of the human reach and therefore requires standards of measure and their mathematical projections, or fore-measure, to bring it within our mindset. We use the mā domain knowledge for this purpose and further extend it to study this pramā region – the antarikś or the vacuum that is inter-galactic or inter-atomic (for here the prefix antar should be understood as inter- or that which is in between). The pratimā can only be imagined and it is that fold which is at the very border of the ‘deducible’ universe. This is the dyauh [15] – it is the nominative-singular of the noun div ( idva ) which literally means the ‘region of light’ or the heaven. (Interestingly it also means ‘to lay a wager, to gamble, to play dice or to bet with’).

Fig. 3.1 from ‘The Artful Universe’ by John D. Barrow (OUP 1995) is reproduced above to show the logarithmic scale, in centimeters, of the universe ‘visible’ to the human consciousness and this extends from the –10 to about +25 decimal power. So dyauh should be interpreted as the ‘observational’ limits imposed in physics by ‘c’ the velocity of light on the higher end and by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle on the lower end. Fig. 3.2 gives these limits as shaded areas viz. the Black Hole and the Quantum Region respectively.

Rig Veda I ,115, 1 – 6 discusses the three realms of the dyauh , antarikś and prithvī in more detail. For further study these shlökas present interesting metaphysical concepts. The trinity here is termed as agnī – the celestial fire, varun – the emanating principle and mitrâ – the attractive principle. This trinity frames the cosmic eye that is illumined by the divine light of sūryâ – the sun.

¥ I will use two more crutches to complete this essay on māyā . Both these minds belong to the list of literary giants of the 20th century.

Firstly, Rabindranath Tagore whose writings are highly influenced by his vedic knowledge. In Gitanjali he says :-

[71] That I should make much of myself and turn it on all sides, thus casting coloured shadows on thy radiance – such is thy maya.

Thou settest a barrier in thine own being and then callest thy severed self in myriad notes. This thy self-separation has taken body in me.

The poignant song is echoed through all the sky in many-coloured tears and smiles, alarms and hopes ; waves rise up and sink again, dreams break and form. In me is thy own defeat of self.

This screen that thou has raised is painted with innumerable figures with the brush of the night and the day. Behind it thy seat is woven in wondrous mysteries of curves, casting away all barren lines of straightness.

The great pageant of thee and me has overspread the sky. With the tune of thee and me all the air is vibrant, and all ages pass with the hiding and seeking of thee and me.

In the poem ‘Ami’ (“I”) in Shyamali, Tagore takes the anthropomorphic view of life and uses the concept of maya to show that Brahman in a state of ‘no-maya’ – a barren , pre-creation existence resorts to ‘yes-maya’ where there is the first desire to create multiplicity, to have man as a colourful presence in the vacuous emptiness. Few paragraphs are extracted here (the complete version with a commentary from “The Concept of Indian Literature” is hyperlinked above) :-

But there is the Infinite One deep in sadhana

in the heart of finite man,

saying, “you and I are one.”

In that oneness of you and I darkness and light become one,

rose shape, rose rasa,

no-maya flowered into yes-maya,

in line and colour, in pain and pleasure.

Don’t call this philosophy,

My heart thrills with the joy of creation

as I stand brush and colour-bowl in hand

in the hall of this cosmic-I…

…The day man disappears

his eyes will take away all the world’s colours.

The day man disappears

his heart will take away all the world’s rasa.

Then Shakti vibrations alone will energise the sky,

there will be no light anywhere.

The musician’s fingers will strum in a veena-less hall

a soundless raga.

A poem-less Creator will sit alone

in a blue bereft sky

lost in the coordinates of a personality-less existence

In terms of space Tagore refers to the –‘ that cosmic mansion stretching across endless and uncountable reaches of space upon space of splendid desolation…’ and in terms of time he writes about the Mahakala time that goes on for yuga upon yuga till the stage of cosmic dissolution when the poem-less Creator will again sit alone in a blue bereft sky lost in the co-ordinates of a personality-less existence. The choice of words here in this poem knit together difficult concepts with soundless ease….

Secondly, Jorge Luis Borges who was an Argentinian short narrative writer with a phenomenal intelligence and knowledge. His writings are filled with metaphysical insights and his inventive style merges mathematical concepts into a simple flow of words. In his essay ‘Avatars of the Tortoise’ (the title is obviously enthused from the second avatār – incarnation of Lord Vishnu [16], the kurma or tortoise) that is based on Archimedes’ paradox about the race between the hare and the tortoise Borges concludes :-

It is venturesome to think that a co-ordination of words (philosophies are nothing more than that) can resemble the universe very much. It is also venturesome to think that of all these illustrious co-ordinations, one of them – at least in an infinitesimal way – does not resemble the universe a bit more than the others. I have examined those which enjoy certain prestige; I venture to affirm that only in the one formulated by Schöpenhauer have I recognized some trait of the universe. According to this doctrine, the world is a fabrication of the will. Art – always – requires visible unrealities. Let it suffice for me to mention one : the metaphorical or numerous or carefully accidental diction of the interlocutors in a drama…..Let us admit what all idealists admit : the hallucinatory nature of the world. Let us do what no idealist has done : seek unrealities which confirm that nature. We shall find them, I believe, in the antimonies of Kant and in the dialectic of Zeno.[17]

‘The greatest magician (Novalis has memorably written) would be the one who would cast over himself a spell so complete that he would take his own phantasmagorias as autonomous appearances. Would not this be our case ?’ I conjecture that is so. We (the undivided divinity operating within us) have dreamt the world. We have dreamt it as firm, mysterious, visible, ubiquitous in space and durable in time; but in its architecture we have allowed tenuous and eternal crevices of unreason which tell us it is false.

Having collated from some of the finest writings on māyā I have attempted here to make the reader see through the veil of words. We must understand that the limits of māyā are like the scrim of Radhakrishnan. To pierce this screen we should illumine the ‘other’ side with venturesome knowledge and accept that both the infinite and the infinitesimal belong to this fuzzy realm. This is also borne out by the Brhadāranyaka Upanishad (V.5.1) which explains that satyam consists of three syllables, sa , ti , yam, the first and the last being real and the second unreal, madhyato anrtam. The fleeting is enclosed on both sides by an eternity which is real.

Another important point that emerges is that māyā is not an illusion but a delusion. We can overcome an illusion by outward knowledge e.g. the cause of a mirage or the straight stick appearing bent in water is determined both by experience and science. Delusion, on the other hand is when we fail to perceive the Divine essence of nature and regard it as a mere mechanical determination unrelated to Brahman. The implication is that the problem of māyā is inherent in the attitude of those who perceive, not in that which is perceived……The term illusion is generic; the term delusion is specific. So long as the individual thinks himself to be a separate atom in this immense universe, so long as he has the idea that he is the chief actor in the stage, he is in the world of māyā,…. When he recognizes the essence of the finite to be in the Infinite, when he realizes that he is but an instrument of a nobler purpose, he will get out of this world of māyā.

To transcend this limit we require an inner search, a repetitive build-up of spiritual energies, a regimen of reinforcing natural harmonies. All this can carry us to the winning ticket that lies just beyond the statistical veil of pratimā.